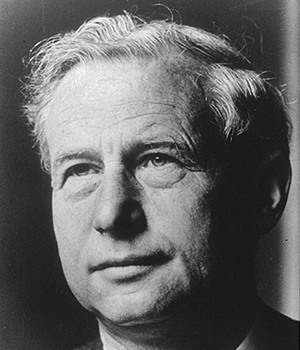

Maurice Henry Pappworth, MD, (1910–1994) was, by any standard, a controversial figure. “A life-long outsider he chose an unconventional career path as a private medical tutor rather than accept anything less than his first job choice — a consultant post in a London teaching hospital.” By all accounts he was rejected because he was a Jew who would not have been accepted by fee-paying patients in Belgravia, Chelsea, and Mayfair. Indeed, when he applied for a post in 1939, he was told that “no Jew could ever be a gentleman. . .”

Maurice Henry Pappworth, MD, (1910–1994) was, by any standard, a controversial figure. “A life-long outsider he chose an unconventional career path as a private medical tutor rather than accept anything less than his first job choice — a consultant post in a London teaching hospital.” By all accounts he was rejected because he was a Jew who would not have been accepted by fee-paying patients in Belgravia, Chelsea, and Mayfair. Indeed, when he applied for a post in 1939, he was told that “no Jew could ever be a gentleman. . .”

He went on to establish himself as an independent medical consultant and tutor in London — a role in which he excelled, helping 1600 junior doctors to pass the grueling Membership of the Royal College of Physicians (MRCP) in post-war London. Though he had passed the MRCP in 1936, it took 57 years for the Royal College of Physicians to accept him as a Fellow of the RCP in 1993. [Wellcome Library Collection]

Dr. Pappworth’s legacy and major contribution — one which has not been fully appreciated — is his contribution to the development of medical research ethics by blowing the whistle on unethical experiments. His concern was aroused by descriptions of experiments in medical journals, and the concerns raised by his postgraduate students who had witnessed, and even participated in such experiments. In 1962 he published fourteen of his letters to medical journal editors; and in 1967, Dr. Pappworth published his book Human Guinea Pigs: Experimentation on Man.

Dr. Pappworth’s legacy and major contribution — one which has not been fully appreciated — is his contribution to the development of medical research ethics by blowing the whistle on unethical experiments. His concern was aroused by descriptions of experiments in medical journals, and the concerns raised by his postgraduate students who had witnessed, and even participated in such experiments. In 1962 he published fourteen of his letters to medical journal editors; and in 1967, Dr. Pappworth published his book Human Guinea Pigs: Experimentation on Man.

“No doctor, however great his capacity or original his ideas, has the right to choose martyrs for science or for the general good.”

He published the book against the advice of the medical establishment who urged him “not to wash the profession’s dirty linen in public.” Dr. Pappworth targeted 205 published experiments, 78 were from the UK and the US that were conducted on vulnerable children, mentally disabled adults and prisoners — his critiques were aimed at deception and violation of informed consent. He indicated that he believed that the experiments were conducted purely for the career advancement of those involved. Not surprisingly, the book attracted vitriolic reviews.

However, it is now regarded as a major milestone in medical ethics; his whistleblowing led the Royal College of Physicians to issue a report on the ethics of experimentation in 1972.

Though not as well known as Dr. Henry Beecher’s 1966 article “Ethics and Clinical Research,” published in the NEJM, Dr. Pappworth — who corresponded with Dr. Beecher and contributed seven of the twenty-two examples cited by Beecher — differed radically from Dr. Beecher in naming the names. Whereas Beecher omitted mentioning any of the researchers or journal references, Pappworth identified the researchers responsible and their institutions. He stood his ground in an invited article in the BMJ, 1990, 301, 1456–60] “My opinion remains that those who dirty the linen and not those who wash it should be criticized. Some do not wash linen in public or in private and the dirt is merely left to accumulate until it stinks.”