Biodefense Stockpile Boondoggle: $334 Million Anthrax Drug

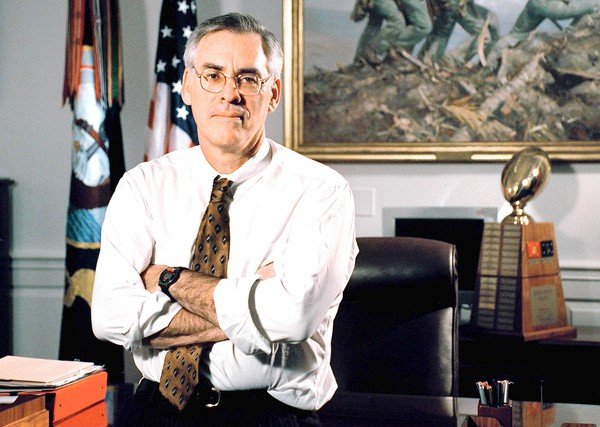

An investigative report by Pulitzer Prize winner, David Willman in the Los Angeles Times, has lifted the lid on the hidden financial conflict of interest of former Navy Secretary Richard Danzing a presidential advisor and a most influential biowarfare consultant to the Pentagon and the Department of Homeland Security whose promotional prodding and recommendation led the Obama Administration to shell out $334 million for an anthrax drug manufactured by the Human Genome Sciences Inc., raxibacumab (raxi) at a cost of $5,100 per dose.

Richard Danzig sat on the board of Human Genome Sciences, the drug’s manufacturer, earning over one million dollars at the same time that he lobbied the administration’s highest level officials urging them to purchase the drug.

“Holy smoke—that was a horrible conflict of interest.”— Dr. Philip K. Russell, on Danzig’s dual roles as corporate director and government advisor.

Danzig’s paper, “Catastrophic Bioterrorism” and invitation only briefings on biological and chemical warfare had enormous influence on US stockpiling biodefense drugs–even though US intelligence agencies have never cited evidence of an anthrax threat, nor established that any nation or terrorist group has made an antibiotic-resistant weapon. Indeed, there is no evidence of a need for this drug, and no justification for the expenditure of hundreds of millions of taxpayer dollars for untested countermeasures against anthrax, given the ready availability and proven 100% effectiveness of antibiotics in the unlikely event of exposure to inhaled anthrax.

The efficacy of raxi in humans is unknown–as it has never been tested in humans. Just like the anthrax vaccine, the shelf life of raxi expires after just 3-years. No other nation has been suckered into purchasing the drug.

The LA Times quotes Danzig stating: “If I thought any of it posed a potential conflict that might cause somebody who knew about it to discount my views, I would tell them.”

The broader implication of the ease with which Mr. Danzig was able to navigate and influence high level administration officials to adopt policies that served his commercial interests, is the demonstrably lax vetting of biodefense consultants and non-cmpetitive biodefense stockpile procurement process that invites corrupt practices and the fleecing of the American taxpayer.

See https://ahrp.org/cms/content/view/904/9/ and see, Getting Rich on Uncle Sucker

Vera Sharav

LOS ANGELES TIMES: Danzig’s twin roles

- May 2001 — Washington lawyer Richard J. Danzig is appointed to the board of Human Genome Sciences Inc. in Rockville, Md.

- Sept. 11, 2001 — Terrorists crash passenger jets into the World Trade Center in New York, the Pentagon and rural Pennsylvania. Soon after, the mailing of anthrax-laced letters to media organizations and congressional leaders sets the nation further on edge.

- Late 2001 — Human Genome Sciences begins testing a compound with the potential to fight antibiotic-resistant anthrax. The work proceeds with Danzig’s encouragement.

- Early 2002 — Danzig, acting as a Pentagon consultant, begins holding invitation-only seminars for U.S. officials on anthrax and other biological threats.

- Spring 2003 — Human Genome announces it is developing a new anthrax drug, raxibacumab, or raxi. Its chief executive tells Congress that “to move forward the company needs a commitment from the federal government” to buy the product.

- August 2003 — Danzig circulates a study he prepared for the Pentagon saying that the U.S. “should give great priority” to stockpiling a drug capable of combating antibiotic-resistant anthrax.

- June 2006 — The government completes its first order for raxi, worth $174 million, and Human Genome’s chief executive calls the contract “a very important contribution to our movement forward as a company.”

- August 2012 — Human Genome is acquired by GlaxoSmithKline for $3.6 billion. By this point, the government has purchased $334 million worth of raxi, and Danzig has collected more than $1 million since 2001 in compensation from the biotech company.

Anthrax drug brings $334 million to Pentagon advisor’s biotech firm

Biowarfare consultant Richard J. Danzig urged the government to stockpile a type of anthrax remedy. But he had a stake in one such drug’s success.

By David Willman Reporting from Washington

May 19, 2013

Over the last decade, former Navy Secretary Richard J. Danzig, a prominent lawyer, presidential advisor and biowarfare consultant to the Pentagon and the Department of Homeland Security, has urged the government to counter what he called a major threat to national security.

Terrorists, he warned, could easily engineer a devastating killer germ: a form of anthrax resistant to common antibiotics.

U.S. intelligence agencies have never established that any nation or terrorist group has made such a weapon, and biodefense scientists say doing so would be very difficult. Nevertheless, Danzig has energetically promoted the threat — and prodded the government to stockpile a new type of drug to defend against it.

Danzig did this while serving as a director of a biotech startup that won $334 million in federal contracts to supply just such a drug, a Los Angeles Times investigation found.

By his own account, Danzig encouraged Human Genome Sciences Inc. to develop the compound, and from 2001 through 2012 he collected more than $1 million in director’s fees and other compensation from the company, records show.

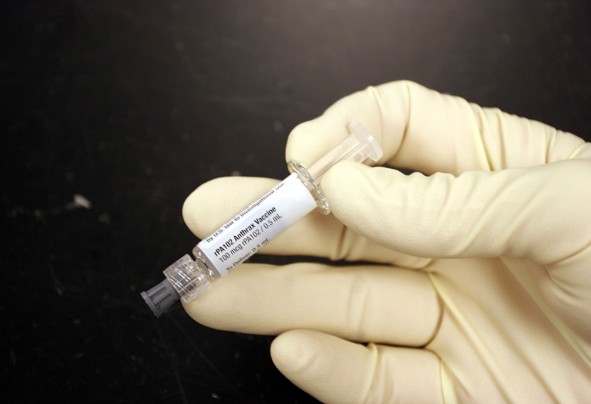

The drug, raxibacumab, or raxi, was the first product the company was able to sell, and the U.S. government remains the only customer, at a cost to date of about $5,100 per dose.

A number of senior federal officials whom Danzig advised on the threat of bioterrorism and what to do about it said they were unaware of his role at Human Genome.

Dr. Philip K. Russell, a biodefense official in the George W. Bush administration who attended invitation-only seminars on bioterrorism led by Danzig, said he did not know about Danzig’s tie to the biotech company until The Times asked him about it.

“Holy smoke—that was a horrible conflict of interest,” said Russell, a physician and retired Army major general who helped lead the government’s efforts to prepare for biological attacks.

“Holy smoke—that was a horrible conflict of interest.” — Dr. Philip K. Russell, on Danzig’s dual roles as corporate director and government advisor

Federal law bars U.S. officials, including consultants, from giving advice on matters in which they or a company on whose board they serve have “a financial interest.”

Danzig said in an interview that he believed his position at Human Genome posed no conflict.

He said he had tried to improve policymakers’ understanding of biodefense issues, including the threat of antibiotic-resistant anthrax, but never lobbied the government to purchase raxi.

“My view was I’m not going to get involved in selling that,” Danzig said. “But at the same time now, should I not say what I think is right in the government circles with regard to this? And my answer was, ‘If I have occasion to comment on this, it ought to be in general, as a policy matter, not as a particular procurement.’

“I feel that I’ve acted very properly with regard to this,” he said.

The government’s purchases of raxi, which began in 2006 under the Bush administration, buoyed the Rockville, Md., company while it struggled to bring a conventional drug to market. The Obama administration has made additional purchases, more than doubling the government’s supply.

Human Genome was acquired by GlaxoSmithKline in August for $3.6 billion.

Because raxi loses its potency after three years in storage, the government’s supply will expire as of 2015, according to federal documents and people familiar with the matter. Administration officials must decide whether to replenish the expiring inventory of raxi and a similar product made by a Canadian company.

Danzig began warning about antibiotic-resistant anthrax after the terrorist attacks of Sept. 11, 2001, and the mailings of anthrax-laced letters that fall.

The powdered anthrax in the letters killed five people but was not resistant to common antibiotics. Asked what gave rise to his concern about resistant strains, Danzig cited conversations with “people whose technical skills exceed mine.” One of them, Dr. Robert P. Kadlec, a bioterrorism advisor in the Bush White House, said he and others were concerned that terrorists could develop such a weapon.

Danzig has sounded the alarm in published papers and in private briefings and seminars for biodefense and intelligence officials.

In a 2003 report fu nded by the Pentagon, “Catastrophic Bioterrorism — What Is To Be Done?” he wrote that it would be “quite easy” for terrorists to produce antibiotic-resistant anthrax. He has expanded on that theme over the years, including in a 2009 paper for the Pentagon.

In the 2003 report, published while raxi was in development at Human Genome, Danzig said a drug to combat resistant strains of anthrax should be produced “as soon as possible” and that stockpiling such a treatment, “even if expensive and in limited supply,” would deter an attack.

John Vitko Jr., a top Homeland Security official during the Bush and Obama administrations, said he turned frequently to Danzig for advice on biodefense matters — and read and “paid attention to” his “Catastrophic Bioterrorism” report.

The two have served for the last seven years on a government panel that provides confidential assessments of the nation’s biodefense needs to the Homeland Security secretary, the National Security Council staff and other senior officials.

Vitko said he knew nothing of Danzig’s involvement with Human Genome until a Times reporter asked him about it.

“I’m surprised I didn’t,” Vitko said. “I’m not aware of it.”

Five other present or former biodefense officials who conferred with Danzig said they, too, had been unaware of his position with the company. Danzig, they said, made no mention of it in their presence during group discussions he led or in smaller meetings.

A seventh person, a former Bush administration official, said Danzig informed him during their first meeting that he was on Human Genome’s board and that the company was developing “a treatment product for anthrax.”

A Times search found seven papers Danzig had written on bioterrorism since 2001. In only one of those did he disclose his tie to Human Genome.

As an advisor to the federal government, Danzig is required to file confidential forms annually, revealing any outside affiliations but not his related compensation. Danzig said he had noted his position with the biotech firm on the forms.

Asked whether he mentioned his corporate role during contacts with government officials, Danzig replied: “If I thought any of it posed a potential conflict that might cause somebody who knew about it to discount my views, I would tell them.”

Danzig, 68, is a Yale Law School graduate and Rhodes scholar who became a partner in Washington for the law firm Latham & Watkins.

He served as a Pentagon appointee during the Carter administration and as undersecretary and then secretary of the Navy under President Clinton. He has a long-standing interest in biowarfare.

During the 2008 presidential campaign, Danzig advised then-Sen. Barack Obama on national security and bioterrorism. After Obama’s election, Danzig was named to the Pentagon’s Defense Policy Board and the President’s Intelligence Advisory Board, in addition to his consulting positions with the Defense Department and Homeland Security.

He has received the Department of Defense Distinguished Public Service Award, the Pentagon’s highest civilian honor, three times — in 1981, 1997 and 2001.

When Human Genome named Danzig to its board on May 24, 2001, the company’s chief executive said his high-level federal experience would “serve us well.”

Later that year, the anthrax letters were mailed to congressional leaders and news organizations, contaminating government buildings in Washington, disrupting mail delivery and causing widespread unease in the wake of the Sept. 11 attacks.

In response, Human Genome began examining experimental compounds under its control — including one to be used against antibiotic-resistant anthrax.

Called an antitoxin, the drug is intended to neutralize anthrax toxin circulating in an infected person’s body. Antibiotics, by contrast, are designed to kill the anthrax bacterium itself.

Danzig recalled his reaction when he learned of the experimental drug, initially called ABthrax, in 2002:

“As a board member, I said, ‘Hey, I think this is a good idea. I think that if you can do this, it will be beneficial both publicly — it’s a good idea to have a drug that does this — and it’ll be economically a good thing for the company.'”

He also began speaking out about the threat posed by anthrax and other biodefense matters.

With support from then-Deputy Defense Secretary Paul Wolfowitz and funding from the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency, Danzig started conducting private briefings and seminars.

Retired Army Maj. Gen. Stephen Reeves, who participated in the sessions while heading the Defense Department’s preparations for biological and chemical warfare, said Danzig presented scenarios related to what he called “reload,” the idea that terrorists might launch a series of anthrax attacks, one after another.

“Then you go around the room to the various people who have any responsibilities in those areas, and say, ‘What are you going to do now, Coach?'” Reeves recalled. “He’s been highly influential in this area, on multiple levels, and across the government.”

Russell, the Bush-era biodefense official, said the sessions, held in 2002 and 2003, galvanized support for stockpiling biodefense drugs.

“Those seminars were attended by all the usual suspects and created a consensus in the thinking about the threat,” Russell said, adding that Danzig “had a major position of influence. People respected his views. He’s a smart guy.”

The anthrax letter attacks, Danzig wrote in his “Catastrophic Bioterrorism” paper, exposed national security vulnerabilities “greater than those associated with 9/11.” He argued that the country’s defenses were inadequate.

Doses of anthrax vaccine would have to be given weeks or months in advance of an attack. As for antibiotics, Danzig suggested that even a novice terrorist could “readily” make a resistant strain.

“Development of an antibiotic-resistant strain … is quite easy,” Danzig wrote. “Even at the high school level, biology students understand that an antibiotic-resistant strain can be developed.”

This is something beyond the capability of a high school student or even someone with graduate training.”— Geneticist Paul Keim,

on developing antibiotic-resistant anthraxSeveral biodefense scientists said in interviews that producing such strains would not be easy.

“It’s not a trivial endeavor,” said Paul Keim, a Northern Arizona University geneticist and anthrax expert. “This is something beyond the capability of a high school student or even someone with graduate training.”

Citing his own published research, Keim said manipulating anthrax to resist antibiotics would decrease the germ’s stability and virulence, typically rendering it nonlethal.

Danzig conceded this possibility in a footnote in “Catastrophic Bioterrorism.” Nonetheless, he wrote that “we should give great priority” to developing “a third alternative” for coping with an anthrax attack.

An antitoxin was such an alternative, he said. It “could be invaluable if we confronted an attack with a strain that was broadly resistant to antibiotics, or if we became aware of the disease too late to treat it only with antibiotics,” he wrote.

Those who would most benefit from a new treatment option, Danzig added, included “the president and his staff, members of Congress, key members of the military.”

In another footnote, Danzig disclosed his connection to Human Genome and its experimental antitoxin:

“As a member of the Board of Directors of Human Genome Sciences, a Nasdaq listed company, I have encouraged the company in its efforts to develop an anthrax antitoxin. I do not believe that my views on this point are distorted by any financial interest, but readers will want to make their own determination. Under any conditions, alternative sources could supply antitoxin, and I make no representation as to which would be the best.”

During his 11-year tenure on the board, which ended in August, Danzig collected at least $1,054,255 in director’s fees and by cashing in grants of Human Genome stock and stock options, according to Fred Whittlesey of Compensation Venture Group, who reviewed the company’s Securities and Exchange Commission filings for The Times.

Nearly half of Danzig’s compensation came from the stock options, of which he had been granted 184,000 by the end of 2011, Whittlesey said.

Danzig also invested his own money in Human Genome, buying 3,000 shares at a cost of $45,955 in May 2002. Danzig said he purchased the stock because “a director ought to have some of his own money at stake,” and that he did not profit from the shares.

On March 18, 2003, Human Genome announced that it was developing raxi as a “mechanism of defense against anthrax,” including antibiotic-resistant strains.

On May 13, Chief Executive William A. Haseltine told the House Homeland Security Committee that “in order to move forward the company needs a commitment from the federal government” to buy raxi.

In late October 2003, he co-hosted a two-day bioterrorism seminar at Aspen Wye River Conference Center, on Maryland’s Eastern Shore, attended by dozens of senior policymakers — including Dr. Anthony Fauci, a director of the National Institutes of Health, and Dr. Julie Gerberding, then-director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Scenarios and recommendations from Danzig’s “Catastrophic Bioterrorism” were a centerpiece of the discussion.

When the government signed its initial order for raxi in June 2006, Human Genome’s new president, H. Thomas Watkins, described its significance.”It’s a very important contribution to our movement forward as a company,” Watkins told Wall Street analysts. “We think it will be a good move for shareholders.”

In 2004, President Bush signed into law Project BioShield, which provided billions of dollars for biodefense drugs.

The contracts are administered by the Department of Health and Human Services, based on advice from federal agencies and consultants. Homeland Security must certify the need for a drug before the government can buy it.

Danzig asserts that terrorists could easily engineer a devastating killer germ: a form of anthrax resistant to common antibiotics.

Danzig, through his seminars, writings and consulting duties, has helped frame the discussion over whether a given biological threat is “material” and whether the government should stockpile medicines to defend against it.

For example, Danzig has served as a member of a Homeland Security review panel that develops the Biodefense Net Assessment, intended to spotlight gaps in the nation’s biological defenses. The panel includes officials from Homeland Security, Health and Human Services, the White House, the Pentagon and the CIA.

Danzig declined to discuss his role in the biodefense assessment or his other government consulting duties.

Vitko, who has chaired the biodefense review panel since its inception in 2006, declined to discuss its work or Danzig’s participation.

Speaking of Danzig’s broader role as a government advisor, Vitko said: “Richard’s got incredible insights into this and I think has made major contributions.”

He called Danzig one of “the major bio players” and said his views had informed a range of policy considerations, including “how many countermeasures do you need, of what kind.”

It was in response to advice from Vitko and his staff that Homeland Security Secretary Tom Ridge in 2004 declared anthrax a “material threat,” the certification required for the government to buy drugs to fight it.

In 2006, the Department of Health and Human Services finalized its first order of raxi — 20,000 doses at a cost of $174 million.

That year, Ridge’s successor, Michael Chertoff, signed a second, more specific declaration, adding “multi-drug-resistant” anthrax to the government’s list of material threats.

Asked the basis for the second declaration, Vitko said: “I think the concern was more forward-looking, and saying, ‘How could the threat evolve, and are we prepared for that?'”

Since 2009, the Obama administration has ordered an additional 45,000 doses of raxi for $160 million.

Danzig has continued to emphasize the threat. In 2009, he warned in a Pentagon-funded report, “A Policymaker’s Guide to Bioterrorism and What to Do About It,” that terrorists could try to “exploit our weaknesses,” adding:

“They could do this, for example, by developing antibiotic-resistant strains when we have stockpiled a particular antibiotic.”

Whether raxi would work as envisioned remains unknown.

Ethical considerations prohibit infecting human volunteers with anthrax. As a result, tests of raxi’s effectiveness were conducted exclusively on animals, which may or may not predict its performance in humans. None of those tests used antibiotic-resistant anthrax.

The FDA approved raxi as an anthrax treatment in December, after an advisory committee voted that it was “reasonably likely” to be effective in humans.

Haseltine, the founding president of Human Genome, said the theoretical threat of terrorist-engineered anthrax had been a key factor in selling the drug to the government.

“They had an empty box: What do you do for antibiotic-resistant anthrax? We were able to fill that box for them,” Haseltine said.