1932–1972: Tuskegee Syphilis experiment

1932–1972: Tuskegee Syphilis experiment, “the longest nontherapeutic experiment on human beings in the history of medicine,” continued unabated 25 years after Nuremberg. Tuskegee Syphilis experiment, “the longest nontherapeutic experiment on human beings in the history of medicine” sponsored by the U.S. Public Health Service continued unabated until 1972 — 25 years after Nuremberg. More than 400 black sharecroppers were observed without treatment so that the government researchers could document the natural course of untreated syphilis in Negro men.

The men were subjected to painful spinal taps and suffer the debilitating disease. When a cure — penicillin — became available in 1947, the doctors failed to provide it. Even the Surgeon General of the U.S. enticed the men to remain in the experiment. By the end of the experiment 28 men had died of syphilis, 100 died of related complications, at least 40 of their wives had been infected, and 19 of their children were born with congenital syphilis. Fifteen scientific reports about this experiment were published in medical journals — but no one in the medical community complained.

Tuskegee came to public attention when Jean Heller, of the Associated Press broke the story, after Peter Buxtun, a former venereal disease interviewer with the Public Health Service blew the whistle.

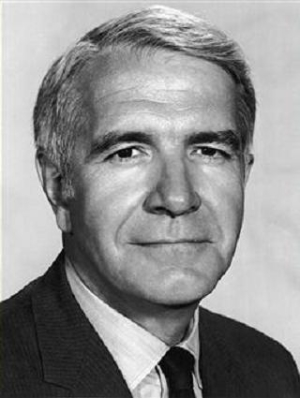

News journalist (ABC and CBS) Harry Reasoner described the “study” as an experiment that “used human beings as laboratory animals in a long and inefficient study of how long it takes syphilis to kill someone.”

News journalist (ABC and CBS) Harry Reasoner described the “study” as an experiment that “used human beings as laboratory animals in a long and inefficient study of how long it takes syphilis to kill someone.”