“Radium Women” Dial Painters: Unwitting Experimental Subjects, 1920 – 1990

Background: In the early part of the twentieth century, radium was a symbol of science, medicine, and technology; power and wealth. Radium was a luminous vehicle for progress, publicly displayed for a week at the Public Health Exposition in Grand Central in New York (1921) to which medical students, physicians and nurses were invited as there was great medical interest in the its potential uses. World War I created a huge demand for a variety of radium-treated devices. Radium was a highly valued investment for the dial painting industry which by 1920 had sold more than 1,000,000 illuminated watches and clocks. (RE Rowland. (Radium in Humans. A Review of U.S. Studies, 1994)

Background: In the early part of the twentieth century, radium was a symbol of science, medicine, and technology; power and wealth. Radium was a luminous vehicle for progress, publicly displayed for a week at the Public Health Exposition in Grand Central in New York (1921) to which medical students, physicians and nurses were invited as there was great medical interest in the its potential uses. World War I created a huge demand for a variety of radium-treated devices. Radium was a highly valued investment for the dial painting industry which by 1920 had sold more than 1,000,000 illuminated watches and clocks. (RE Rowland. (Radium in Humans. A Review of U.S. Studies, 1994)

The first major American manufacturer was Radium Luminous Materials Corp. in New Jersey (renamed U.S. Radium Corp in 1919) which hired young women (mostly teenagers) to apply radium paint to the tiny figures and numbers on clocks, watches, speedometers, compasses, barometers, and dashboard instruments of airplanes, and submarines – so that these instruments would glow in the dark.

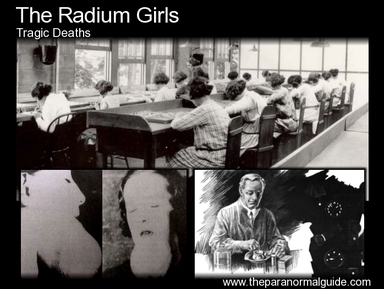

The girls put the paint brushes containing radium-226 between their lips in order to maintain a fine pointed brush tip. As a result, they wound up swallowing a minimum of 125 mg of radioactive fluid each day. The first report of disfiguring jaw necrosis suffered by a 20-year old “dial paint woman” was in December, 1922. After surgical removal of parts of her jaw bone, blood transfusions, and the onset of lung disease, she died in 1923.

The girls put the paint brushes containing radium-226 between their lips in order to maintain a fine pointed brush tip. As a result, they wound up swallowing a minimum of 125 mg of radioactive fluid each day. The first report of disfiguring jaw necrosis suffered by a 20-year old “dial paint woman” was in December, 1922. After surgical removal of parts of her jaw bone, blood transfusions, and the onset of lung disease, she died in 1923.

One after another, the dial painters began to fall ill. Their teeth fell out, their mouths filled with sores, their jaw bones rotted; the frequency of horribly disfiguring cancers of the upper and lower jaw were particularly frightening to women and the cosmetics industry which used radium in some of its products. By 1924, nine dial painters were dead. They were all young women in their 20s who had been healthy, happily painting tiny bright numbers on delicate instruments.

Early example of collaboration by elite academic medical institutions with industry

The U.S. Radium Corp hired academic physicians to provide “scientific evidence” to vindicate the company from liability. Hundreds of young dial painters suffered from a variety of acute disintegrating bones and died painfully. The company hired a doctor from the Industrial Hygiene section at Harvard Medical School (1924) who found no direct cause of harm; the cause was identified as “occupational poisoning.” However, an independent physician, Dr. Frederick Hoffman, named the new disease, “Radium Necrosis” in a paper he delivered at the American Medical Association in May 1925. A New Jersey county medical examiner then conducted an extensive examination of the women; he performed autopsies and described the symptoms, etiology, and pathology of the disease.

A series of law suits followed that were settled out of court for paltry sums. The radium dial industry denied culpability; U.S. Radium Corp hired yet another medical doctor, this time from the Industrial Section of the College of Physicians and Surgeons of Columbia University, who “based on the scientific data acquired [by] Dr. Frederick Flinn [who] reached the conclusion that there was no industrial hazard in the industry.” (A.E. Rowland. Radium in Humans: A Review of U.S. Studies (1994, p. 14)

The tactics used by the radium industry in its legal defense presaged the tactics and strategies of the tobacco industry and the pharmaceutical industry in commissioning academic-affiliated physicians to provide “scientific evidence” denying the severe adverse medical effects of their products. While the radium dial painters were outwitted by industry’s legal and medical team, their plight aroused considerable public outcry and led to the establishment of standards for industrial exposure to ionizing radiation. Under pressure from the New Jersey Consumer’s League, the U.S. Public Health Service finally recommended safe practice radium guidelines in 1933.

The radium dial painters became unwitting human experimental subjects

The radium dial painters became unwitting human experimental subjects

The death of a wealthy steel manufacturer in 1932 who ingested a popular radioactive tonic, called “Radithor,” prompted Robley Evans, a physicist at California Institute of Technology to investigate the safety of radium and to attain expertise in radium safety. Evans was commissioned by the U.S. Army to conduct the first of a series of epidemiological follow-up experiments on the long- term effects of radioactivity in human beings using the women dial painters as his subjects at the Radioactivity Center at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) (1934-1950).

The second phase experiments (1950-1970) were conducted on behalf of the Atomic Energy Committee (AEC) which studied the health risks of atomic tests. The research involved measuring the amount of radium in the women’s bodies; an arduous, repetitive process which Evans’ assistant described as “tough not only on the subject, but it’s tough on the researcher…you have to keep repeating the experiment all over again…” (Dept. of Energy Report, 1995 cited by Maria Rentetzi, 2004) The third phase of research that began after 1970, focused on research by the center for Human Radiobiology at the Argonne National Laboratory (ANL) and the University of Chicago. Eventually all of the radium case studies were centralized at Argone.

In standard medical literature, the radium experiments on the “radium women” are described as an occupational hazard, a “most valuable accident” which has subsequently contributed invaluable information, contributing to the establishment of safety radiation standards. For the researchers, the women were considered a “valuable” means to an end; which was the accumulation of scientific information. This is an immoral utilitarian view that is pervasive among researchers. R.E. Rowland, the author of several ANL human radium studies (1978) and the final review (1994) states in his article posted on the web, Radiaum Dial Painters – What Happened to Them?:

“By the time the final radium study was terminated in 1993, 3,161 radium dial painters had been identified and 1,575 of them had been seen and studied. A total of 6,675 people containing radium had been identified and 2,403 of them had been located and measured.”

Rowland states that the two studies confirmed that dial painters who were employed after 1926, following instructions NOT to tip brushes in on their lips, “was all that was necessary to reduce markedly the amount of radium acquired by these dial painters.” In his Radium in Humans: A Review of U.S. Studies (1994) Rowland cites a report by Schlundt et al, published in 1933, describing an experiment conducted on 32 patients with dementia praecox (i.e., schizophrenia) at Elgin (Illinois) State Hospital who were subjected to radium administered intravenously. As our chronology of medical atrocities amply demonstrates, it was the norm and practice of American physicians to exploit such patients’ vulnerability and use them as human guinea pigs.