Fraudulent Science: What’s Retracted, What’s Not

Critics who deplore the commercialization of medical research have raised concerns about scientific fraud and misconduct that are undermining the integrity of the medical-scientific literature, and thepractice of “evidence-based medicine”— which relies on published journal reports. Recent analyses of retractions of published peer-reviewed journal reports provide supportive evidence for those critics.

Retractions from journals are not routine occurrences–journal editors are extremely reluctant to retract articles, a tacit acknowledgment of their own gate-keeping failure–and fear of reprisals from the sponsors of those retracted trial reports. Many journals don’t even have retraction policies, and the ones that do publish critical notices of retraction long after the original paper appeared—without providing explicit information as to why they are being retracted.

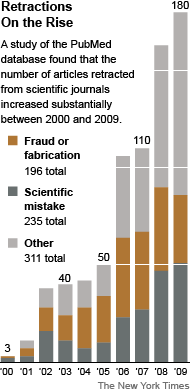

Indeed, the frequency of retractions prompted Ivan Oransky and Ivan Marcus to establish a blog (2010) called “Retraction Watch.” Another website that tracks the PubMed database—by Neil Saunders, an Australian scientist—found that since 1977, the number of retractions increased by a factor of 30, while publications increased fourfold.

Other Retraction Analyses:

In 2006, a letter to the editor, “Top Journals’ Top Retraction Rates,” Shi V. Liu noted that top journals brag about their “high” impact as a commercial strategy to boost circulation and increase their attractiveness to authors. However, the publication of these( later retracted) papers published in high profile journals, “may indicate a real lack of some true scientific criteria for systematically and adequately evaluating manuscripts by these top journals. In fact, as some readers pointed out, some of these top journals base their selection on sensation rather than on science.” Scientific Ethics[3]

In October 2011, the journal Nature [4] reported that published retractions had increased tenfold over the past decade, while the number of published papers had increased by just 44%.

An article by Dr. Grant Steen in the Journal of Medical Ethics (2011) [5] “How Many Patients Are Put at Risk by Flawed Research?” found that retracted papers were cited over 5,000 times, with 93% of citations being research related. This suggests that misinformation promulgated in retracted papers can influence subsequent research.

Dr. Steen analyzed 180 retracted primary studies: 70 of the studies were retracted for fraud, of which 41% were clinical trials involving human subjects ( Steen refers to them as “freshly derived human material”). Over 28 000 subjects had been enrolled, and 9,189 patients were treated. Subsequently, over 400,000 subjects were enrolled in 851 secondary studies which cited a retracted paper—in these secondary studies, 70,501 patients were treated. These estimates, he notes are conservative because only patients enrolled in published clinical studies were counted.

It is worth noting that the results of most negative clinical trials are never published—neither are they disclosed anywhere, except in sponsors’ confidential files and FDA marketing submissions. Those confidential files are pried open ONLY in the course of litigation–until then, commercial stakeholders are shielded by a solid curtain of confidentiality. When post marketing reports link a drug, a medical device or vaccine to serious harm, they are vigorously dismissed as anecdotal, claiming–“there is no scientific evidence” from clinical trials. The evidence and the bodies have been buried without a trace.

The Alliance for Human Research Protection calls upon all medical journals to adopt a publication policy to deter the submission of reports

that misrepresent findings, withhold negative data, or make false, unsubstantiated claims. This is in line with the publication policy adopted by NATURE publications, which have a uniform publication standard:

“A condition of publication in a Nature journal is that authors are required to make materials, data and associated protocols promptly available to others without undue qualifications…Supporting data must be made available to editors and peer-reviewers at the time of submission for the purposes of evaluating the manuscript.”Specifically, for the publication of clinical trials, the Alliance for Human Research Protection recommends that all medical journals require submission of the sponsor’s formal Clinical Study Report which contains the most complete materials, data and associated protocols required by regulatory authorities of the European Union, Japan and the United States (FDA). Inaccuracies, deletions, or alterations in these reports can have regulatory and legal sanctions.

Vera Sharav

References:

- Carl Zimmer, A Sharp Rise in Retractions Calls for Reform, The New York Times, April 16, 2012.

- Ferric C. Fang, Arturo Casadevall, RP Morrison, Retracted Science and the Retraction Index, Infection and Immunity, 2011.

- Liu, S. V. Top Journals’ Top Retraction Rates, Scientific Ethics 1:91–93, 2006;

- Richard Van Noorden, Science Publishing: The Trouble With Retractions, Nature, 2011.

- R Grant Steen, Retractions in the medical literature: how many patients are put at risk by flawed research? J Med Ethics 2011;37:688-6924.

Below, an article by Martha Rosenberg in CounterPunch, cites several rogue journal authors who were sentenced to prison, yet their fraudulent reports continue to pollute the literature. She asks: “If going to prison for research fraud is not enough reason for retraction, what is?”

And the New York Times article by Carl Zimmer.

COUNTERPUNCH

Weekend Edition April 27-29, 2012

According to Science Times[1], the Tuesday science section in the New York Times, scientific retractions are on the rise because of a “dysfunctional scientific climate” that has created a “winner-take-all game with perverse incentives that lead scientists to cut corners and, in some cases, commit acts of misconduct.”

But elsewhere, audacious, falsified research stands unretracted–including the work of authors who actually went to prison for fraud!

Richard Borison, MD, former psychiatry chief at the Augusta Veterans Affairs medical center and Medical College of Georgia, was sentenced to 15 years in prison for a $10 million clinical trial fraud[2] but his 1996 US Seroquel® Study Group research is unretracted.[3] In fact, it is cited in 173 works and medical textbooks, misleading future medical professionals.[4]

Scott Reuben, MD, the “Bernie Madoff” of medicine who published research on clinical trials that never existed, was sentenced to six months in prison in 2010.[5]

But his “research” on popular pain killers like Celebrex and Lyrica is unretracted.[6] If going to prison for research fraud is not enough reason for retraction, what is?Wayne MacFadden, MD, resigned as US medical director for Seroquel in 2006, after sexual affairs with two coworker women researchers surfaced[7], but the related work is unretracted and was even part of Seroquel’s FDA approval package for bipolar disorder.[8]

More than 50 ghostwritten papers about hormone therapy (HT) written by Pfizer’s marketing firm, Designwrite, ran in medical journals, according to unsealed court documents on the University of California–San Francisco’s Drug Industry Document Archive.[9] Though the papers claimed no link between HT and breast cancer and false cardiac and cognitive benefits and were ghostwritten by marketing professionals not doctors, none has been retracted.

Pfizer/Parke-Davis placed 13 ghostwritten articles[10] in medical journals promoting Neurontin for offlabel uses, including a supplement to the Cleveland Clinic[11] but only Cochrane Database Systematic Reviews and Protocols has retracted the specious articles.[12]

Nor is the phony science just a product of “Big Pharma.” In 2008, JAMA was forced to print a correction stating that authors of an article arguing for a higher recommended dietary allowance of protein were, in fact, industry operatives. [13] Sharon L. Miller was “formerly employed by the National Cattlemen’s Beef Association,” and author Robert R. Wolfe, PhD, received money from the Egg Nutrition Center, the National Dairy Council, the National Pork Board, and the Beef Checkoff through the National Cattlemen’s Beef Association, said the clarification. Miller’s email address, in fact was smiller@beef.org, which should might have been the JAMA editors’ first tip-off.[14] The article has also not been retracted.

Martha Rosenberg’s is an investigative health reporter. Her first book, Born With A Junk Food Deficiency: How Flaks, Quacks and Hacks Pimp The Public Health, has just been released by Prometheus books.

Notes.

[1] http://www.nytimes.com/2012/04/17/science/rise-in-scientific-journal-retractions-prompts-calls-for-reform.html

[2] Steve Stecklow and Laura Johannes, “Test Case: Drug Makers Relied on Two Researchers Who Now Await Trial,” Wall Street Journal, August 8, 1997

[3] Richard Borison et al., “ICI 204,636, an Atypical Antipsychotic: Efficacy and Safety in a Multicenter, Placebo-Controlled Trial in Patients with Schizophrenia,” Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology 16, no. 2 (April 1996): 158–69

[4] Alan F. Schatzberg and Charles B. Nemeroff, Textbook of Psychopharmacology (New York: American Psychiatric Publishing, 2009) p. 609

[5] http://www.scientificamerican.com/article.cfm?id=a-medical-madoff-anesthestesiologist-faked-data

[6] Scott Reuben et al., “The Analgesic Efficacy of Celecoxib, Pregabalin, and Their Combination for Spinal Fusion Surgery,” Anesthesia & Analgesia 103, no. 5 (November 2006): 1271–77.

[7] http://www.cbsnews.com/8301-505123_162-42840768/astrazenecas-sex-for-studies-seroquel-scandal-did-research-chief-bias-the-science/

[8] http://www.lifesciencesworld.com/news/view/12152 (BOLDER study)

[9] Martha Rosenberg, “Flash Back. The Troubling Revival of Hormone Therapy. Consumers Digest, November 2010

[10] Kristina Fiore, “Journals Aided in Marketing of Gabapentin,” MedPage Today, September 11, 2009

[11] United States District Court, District of Massachusetts, Report on the Use of Neurontin for Bipolar and Other Mood Disorders,http://i.bnet.com/blogs/neurontin-09513078512.pdf

[12] P. J. Wiffen et al., “WITHDRAWN: Gabapentin for Acute and Chronic Pain,” Cochrane Database Systematic Reviews and Protocols 16, no. 3 (March 16, 2011); P. J. Wiffen et al., “WITHDRAWN: Anticonvulsant Drugs for Acute and Chronic Pain,” Cochrane Database Systematic Reviews and Protocols no. 1 (January 20, 2010);

THE NEW YORK TIMES

April 16, 2012

A Sharp Rise in Retractions Prompts Calls for Reform

By Carl ZimmerIn the fall of 2010, Dr. Ferric C. Fang made an unsettling discovery. Dr. Fang, who is editor in chief of the journal Infection and Immunity, found that one of his authors had doctored several papers.

It was a new experience for him. “Prior to that time,” he said in an interview, “Infection and Immunity had only retracted nine articles over a 40-year period.”

The journal wound up retracting six of the papers from the author, Naoki Mori of the University of the Ryukyus in Japan. And it soon became clear that Infection and Immunity was hardly the only victim of Dr. Mori’s misconduct. Since then, other scientific journals have retracted two dozen of his papers, according to the watchdog blog Retraction Watch.

“Nobody had noticed the whole thing was rotten,” said Dr. Fang, who is a professor at the University of Washington School of Medicine.

Dr. Fang became curious how far the rot extended. To find out, he teamed up with a fellow editor at the journal, Dr. Arturo Casadevall of the Albert Einstein College of Medicine in New York. And before long they reached a troubling conclusion: not only that retractions were rising at an alarming rate, but that retractions were just a manifestation of a much more profound problem — “a symptom of a dysfunctional scientific climate,” as Dr. Fang put it.

Dr. Casadevall, now editor in chief of the journal mBio, said he feared that science had turned into a winner-take-all game with perverse incentives that lead scientists to cut corners and, in some cases, commit acts of misconduct.

“This is a tremendous threat,” he said.

Last month, in a pair of editorials in Infection and Immunity, the two editors issued a plea for fundamental reforms. They also presented their concerns at the March 27 meeting of the National Academies of Sciences committee on science, technology and the law.

Members of the committee agreed with their assessment. “I think this is really coming to a head,” said Dr. Roberta B. Ness, dean of the University of Texas School of Public Health. And Dr. David Korn of Harvard Medical School agreed that “there are problems all through the system.”

No one claims that science was ever free of misconduct or bad research. Indeed, the scientific method itself is intended to overcome mistakes and misdeeds. When scientists make a new discovery, others review the research skeptically before it is published. And once it is, the scientific community can try to replicate the results to see if they hold up.

But critics like Dr. Fang and Dr. Casadevall argue that science has changed in some worrying ways in recent decades — especially biomedical research, which consumes a larger and larger share of government science spending.

In October 2011, for example, the journal Nature reported that published retractions had increased tenfold over the past decade, while the number of published papers had increased by just 44 percent. In 2010 The Journal of Medical Ethics published a study finding the new raft of recent retractions was a mix of misconduct and honest scientific mistakes.

Several factors are at play here, scientists say. One may be that because journals are now online, bad papers are simply reaching a wider audience, making it more likely that errors will be spotted. “You can sit at your laptop and pull a lot of different papers together,” Dr. Fang said.

But other forces are more pernicious. To survive professionally, scientists feel the need to publish as many papers as possible, and to get them into high-profile journals. And sometimes they cut corners or even commit misconduct to get there.

To measure this claim, Dr. Fang and Dr. Casadevall looked at the rate of retractions in 17 journals from 2001 to 2010 and compared it with the journals’ “impact factor,” a score based on how often their papers are cited by scientists. The higher a journal’s impact factor, the two editors found, the higher its retraction rate.

The highest “retraction index” in the study went to one of the world’s leading medical journals, The New England Journal of Medicine. In a statement for this article, it questioned the study’s methodology, noting that it considered only papers with abstracts, which are included in a small fraction of studies published in each issue. “Because our denominator was low, the index was high,” the statement said.

Monica M. Bradford, executive editor of the journal Science, suggested that the extra attention high-impact journals get might be part of the reason for their higher rate of retraction. “Papers making the most dramatic advances will be subject to the most scrutiny,” she said.

Dr. Fang says that may well be true, but adds that it cuts both ways — that the scramble to publish in high-impact journals may be leading to more and more errors. Each year, every laboratory produces a new crop of Ph.D.’s, who must compete for a small number of jobs, and the competition is getting fiercer. In 1973, more than half of biologists had a tenure-track job within six years of getting a Ph.D. By 2006 the figure was down to 15 percent.

Yet labs continue to have an incentive to take on lots of graduate students to produce more research. “I refer to it as a pyramid scheme,” said Paula Stephan, a Georgia State University economist and author of “How Economics Shapes Science,” published in January by Harvard University Press.

In such an environment, a high-profile paper can mean the difference between a career in science or leaving the field. “It’s becoming the price of admission,” Dr. Fang said.

The scramble isn’t over once young scientists get a job. “Everyone feels nervous even when they’re successful,” he continued. “They ask, ‘Will this be the beginning of the decline?’ ”

University laboratories count on a steady stream of grants from the government and other sources. The National Institutes of Health accepts a much lower percentage of grant applications today than in earlier decades. At the same time, many universities expect scientists to draw an increasing part of their salaries from grants, and these pressures have influenced how scientists are promoted.

“What people do is they count papers, and they look at the prestige of the journal in which the research is published, and they see how many grant dollars scientists have, and if they don’t have funding, they don’t get promoted,” Dr. Fang said. “It’s not about the quality of the research.”

Dr. Ness likens scientists today to small-business owners, rather than people trying to satisfy their curiosity about how the world works. “You’re marketing and selling to other scientists,” she said. “To the degree you can market and sell your products better, you’re creating the revenue stream to fund your enterprise.”

Universities want to attract successful scientists, and so they have erected a glut of science buildings, Dr. Stephan said. Some universities have gone into debt, betting that the flow of grant money will eventually pay off the loans. “It’s really going to bite them,” she said.

With all this pressure on scientists, they may lack the extra time to check their own research — to figure out why some of their data doesn’t fit their hypothesis, for example. Instead, they have to be concerned about publishing papers before someone else publishes the same results.

“You can’t afford to fail, to have your hypothesis disproven,” Dr. Fang said. “It’s a small minority of scientists who engage in frank misconduct. It’s a much more insidious thing that you feel compelled to put the best face on everything.”

Adding to the pressure, thousands of new Ph.D. scientists are coming out of countries like China and India. Writing in the April 5 issue of Nature, Dr. Stephan points out that a number of countries — including China, South Korea and Turkey — now offer cash rewards to scientists who get papers into high-profile journals. She has found these incentives set off a flood of extra papers submitted to those journals, with few actually being published in them. “It clearly burdens the system,” she said.

To change the system, Dr. Fang and Dr. Casadevall say, start by giving graduate students a better understanding of science’s ground rules — what Dr. Casadevall calls “the science of how you know what you know.”

They would also move away from the winner-take-all system, in which grants are concentrated among a small fraction of scientists. One way to do that may be to put a cap on the grants any one lab can receive.

Such a shift would require scientists to surrender some of their most cherished practices — the priority rule, for example, which gives all the credit for a scientific discovery to whoever publishes results first. (Three centuries ago, Isaac Newton and Gottfried Leibniz were bickering about who invented calculus.) Dr. Casadevall thinks it leads to rival research teams’ obsessing over secrecy and rushing out their papers to beat their competitors. “And that can’t be good,” he said.

To ease such cutthroat competition, the two editors would also change the rules for scientific prizes and would have universities take collaboration into account when they decide on promotions.

Ms. Bradford, of Science magazine, agreed. “I would agree that a scientist’s career advancement should not depend solely on the publications listed on his or her C.V.,” she said, “and that there is much room for improvement in how scientific talent in all its diversity can be nurtured.”

Even scientists who are sympathetic to the idea of fundamental change are skeptical that it will happen any time soon. “I don’t think they have much chance of changing what they’re talking about,” said Dr. Korn, of Harvard.

But Dr. Fang worries that the situation could be become much more dire if nothing happens soon. “When our generation goes away, where is the new generation going to be?” he asked. “All the scientists I know are so anxious about their funding that they don’t make inspiring role models. I heard it from my own kids, who went into art and music respectively. They said, ‘You know, we see you, and you don’t look very happy.’ ”