Blitzed: Nazi Germany’s methamphetamine addiction

Norman Ohler, an award winning German journalist and author of novels, has written an astonishing historical account that brings to light a previously unmentioned, but pervasive facet of life during the Third Reich. The German book title, Der Totale Rausch“(2015) is a play on Joseph Goebble’s infamous declaration of “total war.” Its title in English is Blitzed: Drugs in Nazi Germany (2016). Ohler spent five years researching the book; he traveled to numerous archives; and gathered a great deal of previously disregarded documentation. What he found overturns yet another myth and misconception about the Nazi regime.

Contrary to how the Nazis portrayed themselves as warriors in a fight against moral degeneracy, the entire German populace was addicted psychotropic drugs. They used cocaine, heroin, morphine, and most popular of all was methamphetamine or crystal meth. Meth was used by everyone, from factory workers, housewives. In an interview in DW Ohler describes German addiction to Pervitin:

“It was freely available as a medicine until 1939.In Berlin, it became a drug of choice, like people drink coffee to boost their energy. People took loads of Pervitin, across the board. The company wanted Pervitin to rival Coca Cola. So people took it, it worked and they were euphoric – a mood that matched the general mood before the war.”

Previtin was used heavily in the German army. The army realized there is a drug out there that might be of interest to soldiers because Pervitin keeps you awake for a long time… for the first couple of days, you don’t need to sleep. It was used for the first time when Germany invaded Sudetenland and then Poland, and then when Germany attacked France in 1940, a Blitzkrieg strategy. Before that attack, the German army ordered 35 million tablets of Pervitin for the soldiers advancing on France. Methamphetamine kept people in the system without their having to think about it.” (Deutsche Welle, 2015)

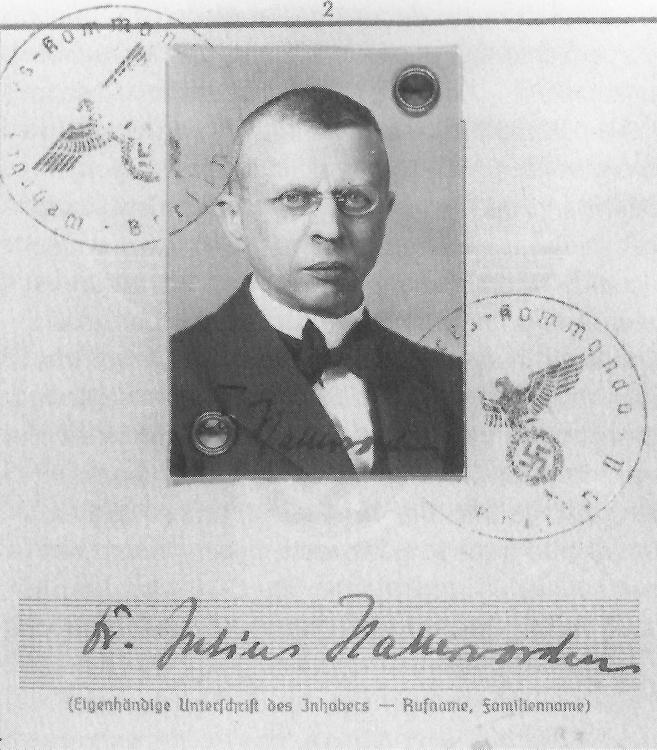

Contrary to the carefully crafted myth about Hitler as an ascetic teetotaler vegetarian, secret medical notes written by Hitler’s personal doctor, Dr. Theodor Morell, who treated Hitler over a period of years, kept Hitler’s addiction secret. In 2013, a National Geographic TV documentary first revealed Hitler’s drug addiction. It too relied on Dr. Morell’s notes. (International Business Times, August 2013)

Hitler didn’t use Pervitin; he was into steroids – animal hormones got injected into his bloodstream. And later he used Eukodal, a pharmaceutical cousin of heroin. Hitler loved Eukodal.

“The Führer was an absolute junkie with ruined veins by the time he retreated to the last of his bunkers – but on the Wehrmacht’s successful invasion of France in 1940.”

Pervitin: “National Socialism in pill form.”

Beneath the surface of an imposed order, according to Ohler, Nazi Germany was a place of complete chaos. In an interview in The Guardian, Ohler described how Dr Fritz Hauschild, the head chemist of the Temmler pharmaceutical company in Berlin, was

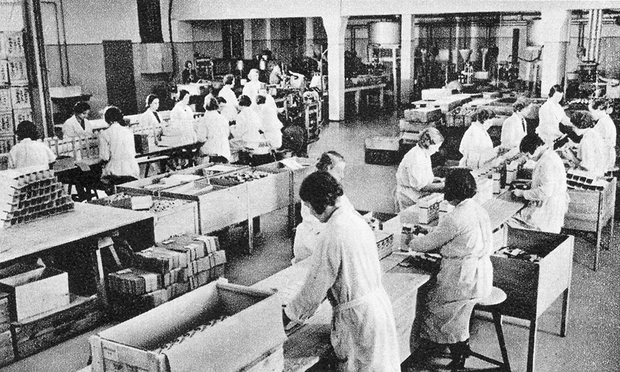

“inspired by the successful use of the American amphetamine Benzedrine at the 1936 Olympic Games, began trying to develop his own wonder drug – and a year later, he patented the first German methyl-amphetamine. Pervitin, as it was known, quickly became a sensation, used as a confidence booster and performance enhancer by everyone from secretaries to actors to train drivers (initially, it could be bought without prescription). It even made its way into confectionery. Hildebrand chocolates are always a delight,” went the slogan. Women were recommended to eat two or three, after which they would be able to get through their housework in no time at all – with the added bonus that they would also lose weight, given the deleterious effect Pervitin had on the appetite.

Pervitin was used against the greatest enemy that soldiers had to deal with, namely; sleep. The job of Dr Otto Ranke, the director of the Institute for General and Defense Physiology, was to protect the Wehrmacht’s “animated machines” – a reference to its soldiers – from exhaustion.

“after conducting some tests he concluded that Pervitin was indeed excellent medicine for exhausted soldiers. Not only did it make sleep unnecessary (Ranke, who would himself become addicted to the drug, observed that he could work for 50 hours on Pervitin without feeling fatigued), it also switched off inhibitions, making fighting easier, or at any rate less terrifying.

In 1940, as plans were made to invade France through the Ardennes mountains, a “stimulant decree” was sent out to army doctors, recommending that soldiers take one tablet per day, two at night in short sequence, and another one or two tablets after two or three hours if necessary. The Wehrmacht ordered 35m tablets for the army and Luftwaffe, and the Temmler factory increased production.”

Ohler believes that the invasion of France was made possible by the drugs. “No drugs, no invasion.”

“When Hitler heard about the plan to invade through Ardennes, he loved it [the allies were massed in northern Belgium]. But the high command said: it’s not possible, at night we have to rest, and they [the allies] will retreat and we will be stuck in the mountains. But then the stimulant decree was released, and that enabled them to stay awake for three days and three nights. Rommel [who then led one of the panzer divisions] and all those tank commanders were high – and without the tanks, they certainly wouldn’t have won.”

Thereafter, drugs were regarded as an effective weapon by high command, one that could be deployed against the greatest odds. In 1944-45, for instance, when it was increasingly clear that victory against the allies was all but impossible, the German navy developed a range of one-man U-boats; the fantastical idea was that these pint-sized submarines would make their way up the Thames estuary.

But since they could only be used if the lone marines piloting them could stay awake for days at a time, Dr Gerhard Orzechowski, the head pharmacologist of the naval supreme command on the Baltic, had no choice but to begin working on the development of a new super-medication – a cocaine chewing gum that would be the hardest drug German soldiers had ever taken. It was tested at the Sachsenhausen concentration camp, on a track used to trial new shoe soles for German factories; prisoners were required to walk – and walk – until they dropped.

“It was crazy, horrifying,” says Ohler, quietly. “Even Mommsen was shocked by this. He had never heard about it before.” The young marines, strapped in their metal boxes, unable to move at all and cut off from the outside world, suffered psychotic episodes as the drugs took hold, and frequently got lost, at which point the fact that they could stay awake for up to seven days became irrelevant. “It was unreal,” says Ohler. “This wasn’t reality. But if you’re fighting an enemy bigger than yourself, you have no choice. You must, somehow, exceed your own strength. That’s why terrorists use suicide bombers. It’s an unfair weapon. If you’re going to send a bomb into a crowd of civilians, of course you’re going to have a success.” (The Guardian, Sept. 25, 2016)

Ohler, who was born in 1970, recalls how his maternal grandfather, a railway engineer during the war, acknowledged having once seen a cattle train and hearing children’s voices from within. Like most Germans, his grandfather often said “Hitler wasn’t so bad… In the 1980s you used to hear that a lot: that it was all exaggerated, that Hitler didn’t know about the bad things, that he created order.”

Ohler hopes that his book will be read by a younger generation of Germans who would rather look to the future than dwell on the past. “It is quite a dangerous time. I hate these attacks on foreigners, but then our governments do it, too, in Iraq and places. Our democracies haven’t done a very good job in this globalised world.”