Presidential Panel Condemns US Syphilis Study in Guatemala

A year after professor Susan M. Reverby, a historian at Wellesley College in Massachusetts, uncovered a heinous Guatemalan syphilis experiment conducted between 1946 and 1948, on at least 5,500 under the auspices of the US Public Health Service, a hearing was held this week about the findings of the President’s Bioethics Commission investigation.

The Commission confirms that despite knowledge that it was unethical, US government medical scientists PURPOSELY infected "at least 1,300 who were exposed to the sexually transmitted diseases syphilis, gonorrhea and chancroid" to study the effects of penicillin. At least 83 subjects died."

THE NEW YORK TIMES, 1947:

"They infected soldiers, prostitutes, prisoners and mental patients. More than 5,500 people in all were part of the medical experimentation.And the presidential panel said government scientists knew they were violating ethical rules."

The research "included infecting prisoners by bringing them prostitutes who were either already carrying the diseases or were purposely infected by the researchers. Doctors also poured bacteria onto wounds they had opened with needles on prisoners’ penises, faces and arms. In some cases, infectious material was injected into their spines, the commission reported."

None of those who were drafted volunteered or consented to the experiment.

One such victimized human being was a mental patient named Berta.

"She was first deliberately infected with syphilis and, months later, given penicillin. After that, Dr. John C. Cutler of the Public Health Service, who led the experiments, described her as so unwell that she “appeared she was going to die.” Nonetheless, he inserted pus from a male gonorrhea victim into her eyes, urethra and rectum. Four days later, infected in both eyes and bleeding from the urethra, she died."

“Actually cruel and inhuman conduct took place,” said Anita L. Allen, a bioethicist at the University of Pennsylvania’s law school. “These are very grave human rights violations.”

Those subjected to these gruesome experiments "were poor, handicapped or imprisoned Guatemalans. They were chosen because they were “available and powerless.”

BBC reported on March 14, 2011 that the researchers bribed care workers to let them infect their charges and prisoners were encouraged to sleep with infected prostitutes.

Members of the President’s Commission concluded that “These researchers knew these were unethical experiments, and they conducted them anyway,” said Raju Kucherlapati of Harvard Medical School, a commission member. “That is what is reprehensible.”

Another panelist, John Arras, a bioethicist at the University of Virginia, stated: “I really do believe that a very rigorous judgment of moral blame can be lodged against some of these people.”

The primary investigator of a series of inhumane, government-sponsored, syphilis experiments was John C. Cutler. He and his team of US scientists conducted syphilis experiments on US prisoners at Terre Haute, Indiana, and at Sing Sing, New York; on poor African-American men with late-stage syphilis at Tuskegee, denying them treatment until 1973; and they deliberately infected mental patients and prisoners in Guatemala, causing 83 deaths.

PubMed, the database for medical-scientific journal articles, lists John C. Cutler as the author on 58 journal articles published between 1946 and 1995. He died without ever being held accountable, in 2003.

The study was carried out by US scientists between 1946 and 1948. Researchers bribed care workers to let them infect their charges and prisoners were encouraged to have sex with infected prostitutes.

The experiment is acknowledged to be "much worse than Tuskegee."

On Oct 2010 the US Apologized to the current Guatemalan government and President Obama oordered an investigation , on Nov 2010.

Today, profit–not cure–reins supreme in medical research. The major sponsors of current medical experiments–which are referred to as "clinical trials"–are the pharmaceutical companies whose singular goal is to obtain FDA approval for marketing their products.Most new drugs are "me too" copy cats that offer no improvement, but all too often result in serious harm.

Arthur Caplan. director of the Bioethics Center at the University of Pennsylvania–a center whose dependency on pharmaceutical industry funding is legendary–is hardly someone who is objective. He tried to shield his benefactors by claiming: "I don’t think the pharmaceutical companies are running around giving people diseases or operating in prisons or mental asylums."

To gain an objective, evidence-based perspective, one must turn to evidence gathered by lawyers during litigation, by independent, ethicists who are not industry’s academic shills, such as Carl Elliott: Useless Studies, Real Harm, The New York Times, and Making a Killing–Marketing Exercises; and investigative reports–such as, Vanity Fair: Deadly Medicine: Foreign Clinical Trials, Bloomberg News: Big Pharma’s Shameful Secret and Montreal Clinical Trial Subjects Exposed to Tuberculosis ; PBS: "Bitter Pill" Based on Bloomberg Pharma’s Shameful Secret Report, The Washington Post: Pfizer Faulted-1996 Clinical Trials In Nigeria: Unapproved Drug Tested On Kids…

The weakness of the current regulatory system is acknowledged by most independent analysts without financial ties to industry. The trials lack independent review and oversight, and human subjects continue to be mostly the poor and disenfranchised. Furthermore, many experiments fail to meet valid ethical and scientific justification.

New drugs brought to market are mostly "me too" copy-cats that do NOT improve medical outcomes. Indeed, numerous drugs have been pulled from the market after they killed or maimed patients.

Ironically, in July, the US government, under the Obama Administration, issued proposed regulatory changes (92 pp.) that would (essentially) eviscerate the very regulatory legal protections that were adopted in the wake of the revelations about the unethical conduct of the Tuskegee syphilis experiment.

This week the President’s Bioethics Commission urged the US to join the rest of the civilized world, by ADDING compensation requirements for the protection of human research subjects–either directly or through mandatory insurance.

“The panel felt strongly that it was wrong and a mistake that the United States was an outlier in not specifying any system for compensation for research subjects other than, ‘You get a lawyer and sue.’”

Below, ABC News: Syphilis Experiments Shock, But So Do Third World Drug Trials

The New York Times: Panel Hears Grim Details of Venereal Disease Tests

The Washington Post: Compensation system urged for research victims

Read more at:

The Washington Post: U.S. scientists knew 1940s Guatemalan STD studies were unethical, panel finds

U.S. apologizes for newly revealed syphilis experiments done in Guatemala

BBC News: US scientists ‘knew Guatemala syphilis tests unethical’

Al Jazeera: Panel condemns US syphilis study in Guatemala

Vera Hassner Sharav

ABC News

Syphilis Experiments Shock, But So Do Third World Drug Trials

A commission set up last year by President Barack Obama has revealed that 83 Guatemalans died in U.S. government research that infected hundreds of prisoners, prostitutes and mental patients with the syphilis bacteria to study the drug penicillin — a project that the group called "a shameful piece of medical history."

"The report is good and I applaud the Obama administration for giving it some sunshine," said Dr. Howard Markel, a pediatrician and medical historian from the University of Michigan. "Internationally, what we do as a human society is to make sure that these things never happen again."

But medical ethicists say that even if today’s research is not as egregious as the Guatemala experiment, American companies are still testing drugs on poor, sometimes unknowing populations in the developing world.

Many, like Markel, note that experimenting with AIDS drugs in Africa and other pharmaceutical trials in Third World countries, "goes on every day."

"It’s not good enough, in my opinion, to protect only people who live in the developed world — but all human beings," he said.

The U.S. Public Health Service and the Pan American Sanitary Bureau worked with several Guatemalan government agencies from 1946 to 1948, exposing about 1,300 people to the sexually transmitted diseases syphilis, gonorrhea or chancroid.

Getty ImagesThe Presidential Commission for the study of Bioethical Issues revealed shocking new details of U.S. syphilis experiments in Guatemala in the 1940s.HPV and Men Watch VideoAIDS Vaccine Breakthrough? Watch VideoRemembering an ‘Ace’ Tuskegee Airman Watch Video

Getty ImagesThe Presidential Commission for the study of Bioethical Issues revealed shocking new details of U.S. syphilis experiments in Guatemala in the 1940s.HPV and Men Watch VideoAIDS Vaccine Breakthrough? Watch VideoRemembering an ‘Ace’ Tuskegee Airman Watch VideoThey infected soldiers, prostitutes, prisoners and mental patients. More than 5,500 people in all were part of the medical experimentation.

And the presidential panel said government scientists knew they were violating ethical rules.

Scientists wanted to see if penicillin, which was a relatively new drug, could prevent infections. The research was paid for with U.S. tax dollars and culled no useful medical information.

This week the Obama commission revealed that only 700 of them received treatment and 83 died by 1953. The commission could not confirm whether the deaths were a direct cause of those infections.

In the 1940s, syphilis was a major health threat, causing blindness, insanity and even death.

Many of the same researchers had carried out studies on prisoners in Terre Haute, Indiana, but unlike the Guatemalan patients, the Americans gave consent.

For years, the experiments were secret, until a medical historian at Wellesley College in Massachusetts found the records among the papers of Dr. John Cutler, who led the experiments. A federal commission to learn more was set up last year.

According to Markel, ethical considerations in science began to emerge after World War II, and further enlightenment followed after the American civil rights movement.

"This was far too common a phenomenon until our recent history — in the prison population and homes for the mentally retarded," he said. "Part of the reason we did this research is we didn’t think of them as humans."

The discovery of the Holocaust and the murder of 6 million people — Jews, the disabled, homosexuals and gypsies, as well as bad experimentation by Nazi doctors, opened the world’s eyes.

The founding of the United Nations and the World Health Organization also brought attention to human rights.

"Each new discovery and advance in social rights, we had to learn the lesson over and over again," he said. "For a long time, blacks were second or third class citizens."

Tuskegee Project Continued Until 1972

One government project that infected black men in Tuskegee, Ala., continued up until 1972 when an Associated Press story on the project caused public outrage.

In 1932, the Public Health Service, working with the Tuskegee Institute, began a study to record the natural history of syphilis in hopes of justifying treatment programs for blacks.

The study initially involved 600 black men — 399 with syphilis, 201 who did not have the disease. The study was conducted without the benefit of patients’ informed consent.

Like the Guatemalans under experimentation, they never received any treatment to cure their illness.

"Some people ask if what went on in Guatemala could go on today, and I say I don’t think so," said Arthur Caplan, director of the Center for Bioethics at the University of Pennsylvania. "I don’t think the pharmaceutical companies are running around giving people diseases or operating in prisons or mental asylums."

But today, drug companies hoping to speed up their Phase 3 clinical trials and get Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval go to developing countries to find an abundance of poor patients will to try new drugs.

"Giving people a fatal disease is the worst thing you can do," according to Caplan, who said ethical questions are also raised when "we give poor people medicine for a disease they might have, and leave and sell [the drugs] in the U.S."

Remembering an ‘Ace’ Tuskegee Airman Watch Video

He said there are also no internationally enforceable standards for such research. "The world doesn’t have any rules," said Caplan.

About a decade ago when the human genome was being mapped, companies were excited about exploring new drug options, and private funding expanded.

"We began to see big money come from pharma, intended to sell in the developing world but trying it out in poor nations because it could be done cheaply and faster. They face less vigorous regulatory oversight," he said.

The key to protection is informed consent. If a patient is in a placebo group and not getting the drug, they need to know that, he said.

"If they have no education and they are bedazzled to see a doctor for the first time, they may not be listening," said Caplan. "Informed consent at its best is dubious in poor countries."

Existing treatment that works on a disease should never be held back, he said. "If you come to test a diabetes drug among poor people in India and given them a placebo and not insulin, you are exploiting them, especially if you are going to sell the drug only in Europe and Canada and they get to use it for a while and then you leave."

Drugs should also be made available once the study concludes, according to Caplan.

"And if the country is so corrupt the drugs get stolen on the black market, we should commit building a water treatment plant or a clinic or make a road," he said.

And those who don’t think about where their drugs are tested should think twice, he said.

"It’s the same phenomenon: ‘I can get really cheap clothes made by sweat shop in labor in China. I am not asking how it’s made, I just like the low price,’" said Caplan. "The stance we take toward the poor is they matter less."

Prisoners, like those infected with syphilis in Guatemala are often poorly education and "easily coerced," said Caplan.

Meanwhile, Guatemala’s Vice President Rafael Espada said his government would make a formal apology to his people because local doctors had also been involved in the U.S.-funded program.

President Obama has also apologized to Guatemalan President Alvaro Colom. A final report is due in December.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

August 30, 2011

THE NEW YORK TIMES

Panel Hears Grim Details of Venereal Disease Tests

By DONALD G. McNEIL Jr.

Gruesome details of American-run venereal disease experiments on Guatemalan prisoners, soldiers and mental patients in the years after World War II were revealed this week during hearings before a White House bioethics panel investigating the study’s sordid history.

From 1946 to 1948, American taxpayers, through the Public Health Service, paid for syphilis-infected Guatemalan prostitutes to have sex with prisoners. When some of the men failed to become infected through sex, the bacteria were poured into scrapes made on the penises or faces, or even injected by spinal puncture.

About 5,500 Guatemalans were enrolled, about 1,300 of whom were deliberately infected with syphilis, gonorrhea or chancroid. At least 83 died, but it was not clear if the experiments killed them. About 700 were treated with antibiotics, records showed; it was not clear if some were never treated.

The stated aim of the study was to see if penicillin could prevent infection after exposure. But the study’s leaders changed explanations several times.

“This was a very dark chapter in the history of medical research sponsored by the U.S. government,” Amy Gutmann, the chairwoman of the bioethics panel and the president of the University of Pennsylvania, said in an interview.

President Obama apologized to President Álvaro Colom of Guatemala for the experiments last year, after they were discovered.

Since then, the panel, the Presidential Commission for the Study of Bioethical Issues, has studied 125,000 pages of documents and has sent investigators to Guatemala. While the panel will not make its final report until next month, details emerged in hearings on Monday and Tuesday.

The most offensive case, said John Arras, a bioethicist at the University of Virginia and a panelist, was that of a mental patient named Berta.

She was first deliberately infected with syphilis and, months later, given penicillin. After that, Dr. John C. Cutler of the Public Health Service, who led the experiments, described her as so unwell that she “appeared she was going to die.” Nonetheless, he inserted pus from a male gonorrhea victim into her eyes, urethra and rectum. Four days later, infected in both eyes and bleeding from the urethra, she died.

“I really do believe that a very rigorous judgment of moral blame can be lodged against some of these people,” Dr. Arras said.

Also, several epileptic women at a Guatemalan home for the insane were injected with syphilis below the base of their skull. One was left paralyzed for two months by meningitis.

Dr. Cutler said he was testing a theory that the injections could cure epilepsy.

Poor, handicapped or imprisoned Guatemalans were chosen because they were “available and powerless,” said Anita L. Allen, a bioethicist at the University of Pennsylvania’s law school and a panelist.

The panel’s hearings also brought to light that a local doctor had invited the American researchers, and that Guatemalan military and health officials had initially approved the work. In 1947, an international conference on venereal diseases — based on the experiments — was held in Guatemala City, according to Dr. Rafael Espada, the vice president of Guatemala, in remarks quoted by the Guatemalan news media.

Dr. Espada, a physician, is leading his country’s inquiry into the matter and is expected to deliver his report in October. On Monday, he told Guatemalan reporters that five survivors, all in their 80s, had been found and would receive medical tests.

Dr. Cutler’s team took pains to keep its activities hidden from what one of the researchers described as “goody organizations that might raise a lot of smoke.”

Members of the bioethics commission recalled Nazi experiments on Jews and said that Dr. Cutler, who died in 2003, must have known from the Nuremberg doctors’ trials under way by 1946 that his work was unethical.

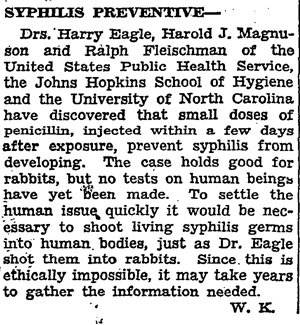

Also, according to Dr. Gutmann, Dr. Cutler had read a brief article in The New York Times on April 27, 1947, about other syphilis researchers — one of them from his own agency — doing tests like his on rabbits. The article stated that it was “ethically impossible” for scientists to “shoot living syphilis germs into human bodies.” His response, Dr. Gutmann said, was to order stricter secrecy about his work.

Also, one commission member added, “Regardless what you think of the ethical issues, it was just bad science.” The results were never published in medical journals, note-keeping was “haphazard at best” and routine protocols were not done.

The Guatemala experiments came to light only last year when a medical historian found descriptive notes in the archives of the University of Pittsburgh. The historian, Susan M. Reverby of Wellesley College, was researching the infamous Tuskegee study, in which Alabama sharecroppers infected with syphilis were left untreated from 1932 to 1972. Dr. Cutler oversaw the Tuskegee study after his Guatemala work finished; he was also an acting dean at the University of Pittsburgh in the 1960s.

Dr. Cutler sent his Guatemala reports to only one supervisor, but Dr. Gutmann said they went up the chain to Surgeon General Thomas Parran Jr., a favorite of President Franklin D. Roosevelt. According to a government biography, Dr. Parran was famous for his long campaign against syphilis, which was then a major public health problem but could not even be mentioned on the radio.

In 1943, Dr. Cutler’s team had tried to infect 241 inmates of a federal prison in Terre Haute, Ind., with gonorrhea. But that time they adhered to ethical protocols, using only volunteers, explaining the risks and offering cash or help getting reduced sentences in return for participating.

Dr. Nelson L. Michael, an AIDS researcher at the Walter Reed Army Institute of Research and a panelist, speculated that the research was rushed and badly done because it had started under intense pressure to help the war effort. Curing troops’ venereal diseases was a major goal of military medicine.

The panelists generally agreed that the ethical review boards now mandated by the American government, universities, foundations and medical journals would prevent similar abuses today by anyone spending taxpayer or foundation money.

Pharmaceutical and medical device companies also do research in poor countries and still need watching, panel members said. But large companies say publicly that they adhere to ethical principles.

“The problem in 1946,” Dr. Gutmann said, “was that ethical rules were treated as obstacles to overcome, not as fundamental bedrock of human dignity. That can still apply today. That’s why our panel is doing our report.”

Panel members endorsed the idea of creating compensation funds for subjects who are harmed in the future, or requiring researchers to buy insurance for that purpose. Some countries require these steps; the United States does not.

Elisabeth Malkin contributed reporting.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

THE WASHINGTON POST

Compensation system urged for research victims

By Rob Stein,

The United States should create a system to compensate people who are harmed by participating in scientific research, a panel of federal advisers recommended Tuesday.

Many other countries require sponsors of studies and researchers to carry insurance for research-related injuries or have other ways to compensate volunteers who are harmed, making the United States an “outlier,” the subcommittee of the Presidential Commission for the Study of Bioethical Issues concluded.

“The panel felt strongly that it was wrong and a mistake that the United States was an outlier in not specifying any system for compensation for research subjects other than, ‘You get a lawyer and sue,’” said Amy Gutmann of the University of Pennsylvania, who chairs the commission and served on the subcommittee.

The recommendation came on the second day of a two-day public hearing to air the results of a commission probe into medical experiments that the U.S. government researchers conducted in Guatemala in the 1940s.

The recently uncovered studies involved more than 5,500 men, women and children who were unwittingly drafted into tests involving the venereal diseases syphilis, gonorrhea and chancroid. The tests included deliberately — sometimes grotesquely — attempting to infect subjects without their permission or knowledge.

On Monday, the commission revealed that the researchers had obtained consent first before conducting earlier, similar experiments on inmates in Terre Haute, Ind., and hid what they were doing in Guatemala. This, the commission found, clearly showed that the doctors knew their conduct was unethical.

In the government-sponsored studies conducted in Guatemala between 1946 and 1948, doctors tried to infect prisoners, soldiers and mental patients by giving them prostitutes who were carrying the diseases or were infected by the researchers. The researchers also scraped sensitive parts of subjects’ anatomy to expose wounds to disease-causing bacteria, poured infectious pus into subjects’ eyes, and injected some victims’ spines.

On Tuesday, the 13-member commission discussed the 48-page report outlining the findings of a 14-member international subcommittee investigating whether current rules adequately protect people in medical studies from physical harm or unethical treatment internationally.

The experts in bioethics and biomedical research from India, Uganda, China, Russia, Brazil, Argentina, Belgium Guatemala, Egypt and the United States met in London, Washington and Philadelphia and made five broad recommendations.

“The United States should implement a system to compensate research subjects for research related injuries,” said Christine Grady of the National Institutes of Health, who helped present the findings of the subcommittee. “Many countries around the world and some U.S. research institutions have actually moved forward and developed compensation systems.”

One “promising model” for a compensation system could be the U.S. National Vaccine Injury Compensation Program, a no-fault alternative to traditional lawsuits that compensates people injured by vaccines, the panel said.

India and Brazil have bioethics committees that “ensure that research sponsors pay compensation to participants injured in research,” the panel wrote. The University of Washington uses a “self-insured no-fault” system.

President Obama ordered the probe when the experiments were made public in October along with an unusual public apology by his secretaries of state and health and human services.

After filing a report in September, the commission will meet again in November to come up with ways to bolster protections for research subjects internationally and in the United States. It will issue a final report in December. The Guatemalan government is conducting its own investigation, but has twice postponed briefing the commission.

Wellesley College historian Susan M. Reverby uncovered the disturbing experiments while reading papers from John C. Cutler, a doctor with the federal government’s Public Health Service. Cutler participated in the Tuskegee experiment, in which hundreds of African American men with syphilis in Alabama were left untreated to study the disease between 1932 and 1972. Cutler died in 2003.

In the Guatemala case, about 700 of the subjects were treated, but it remains unclear whether their care was adequate. About 83 of the subjects died, but investigators have been unable to determine whether any deaths were caused by the studies.