Thomas Szasz, MD (1920–2012)

Thomas Szasz, MD, “Psychiatrist Who Led Movement Against His Field” — He trained at the Chicago Institute for Psychoanalysis; served in the military at the US naval hospital, Bethesda; but “felt viscerally upset” by “the dehumanized language of psychiatry and psychoanalysis.”

Thomas Szasz, MD, “Psychiatrist Who Led Movement Against His Field” — He trained at the Chicago Institute for Psychoanalysis; served in the military at the US naval hospital, Bethesda; but “felt viscerally upset” by “the dehumanized language of psychiatry and psychoanalysis.”

His 1961 book The Myth of Mental Illness questioned the legitimacy of his field; Dr. Szasz saw psychiatry’s medical foundation as shaky at best, placing the discipline “in the company of alchemy and astrology.” The book became a sensation in mental health circles, as well as a bible for those who felt misused by the mental health system and provided the intellectual grounding for generations of critics, patient advocates and antipsychiatry activists, making enemies of many fellow doctors.

He did not publish his heretical ideas on mental illness until he had obtained tenure as professor of psychiatry at the Upstate Medical Centre of the State University of New York, in Syracuse. He taught psychiatry, he said, as an atheist might teach theology. He wrote hundreds of articles and more than 30 books, including Ideology and Insanity: Essays on the Psychiatric Dehumanization of Man (1970) and Psychiatric Slavery: When Confinement and Coercion Masquerade as Cure (1977).

He did not publish his heretical ideas on mental illness until he had obtained tenure as professor of psychiatry at the Upstate Medical Centre of the State University of New York, in Syracuse. He taught psychiatry, he said, as an atheist might teach theology. He wrote hundreds of articles and more than 30 books, including Ideology and Insanity: Essays on the Psychiatric Dehumanization of Man (1970) and Psychiatric Slavery: When Confinement and Coercion Masquerade as Cure (1977).

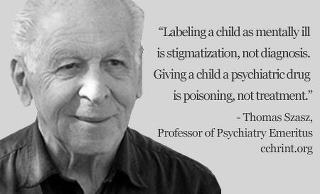

Szasz’s primary concern was the use of the metaphor of mental illness to give false legitimacy to compulsory psychiatry — coercing the innocent — and the insanity defense — excusing the guilty. He denounced these complementary uses of psychiatry as a crime against humanity and called for them to be legally abolished. To his supporters, Szasz was a great existential and libertarian thinker who explored the consequences of a commitment to personal responsibility and freedom in many fields.

His opponents said that he was so obsessed with abstract justice, freedom and responsibility that he denied the medical problems of suffering patients whose mental illnesses made them unable to take responsibility. But Szasz was deeply concerned with human suffering. His point was simply that suffering was not necessarily a medical problem, did not imply lack of responsibility and should not be treated forcibly.

Others acknowledged his critical stand against what they called abuses of psychiatry, but rejected his view that compulsory psychiatry is itself an abuse. They argued that mental illness is indeed illness and may justify compulsion, and that Szasz was irresponsible in denying this.

It is not generally realized how committed he was to voluntary psychotherapy. At a seminar in 2007 he said: “Psychotherapy is one of the most worthwhile things in the world.” But he disagreed with Freud who had described psychotherapy as a science and medical treatment. Szasz viewed psychotherapy as a conversation between consenting adults.

He saw compulsory psychiatry, no matter how compassionately intended, as patronizing and infantilizing. Many observers find that his description of the ever-increasing medicalization of many human situations — what he termed the “therapeutic state” — remains uncannily accurate.

He was controversial to the end; his views were challenged from various angles by leading psychiatrists and philosophers. Szasz was a courteous listener and greatly enjoyed dialogue. He preferred it to lecturing, though he was a brilliant speaker. He published 11 books after turning 80, and conducted an electrifying all-day seminar in London at 90. [Excerpted from obituaries in The New York Times and The Guardian, 2012]

He was controversial to the end; his views were challenged from various angles by leading psychiatrists and philosophers. Szasz was a courteous listener and greatly enjoyed dialogue. He preferred it to lecturing, though he was a brilliant speaker. He published 11 books after turning 80, and conducted an electrifying all-day seminar in London at 90. [Excerpted from obituaries in The New York Times and The Guardian, 2012]