Ravensbrück: the “exclusive” SS women’s concentration camp

Ravensbrück was a concentration camp built exclusively for women. . It was designed to terrorize, brutalize, humiliate, torture & murder. During its six year operation, from 1939–1945, an estimated 132,000 women were imprisoned there; only 15,000 are estimated to have survived. Ravensbrück was built after six major concentration camps were already in operation to meet the need of imprisonment for the large number of women who were incarcerated following the criminalization of prostitution, abortion and sexual relations between Aryan Germans and non-Aryans, as well as political adversaries. (A Holocaust Crossroads: Jewish Women and Children in Ravensbrück, edited by Irith Dublon Knebel, 2010)

Ravensbrück was a concentration camp built exclusively for women. . It was designed to terrorize, brutalize, humiliate, torture & murder. During its six year operation, from 1939–1945, an estimated 132,000 women were imprisoned there; only 15,000 are estimated to have survived. Ravensbrück was built after six major concentration camps were already in operation to meet the need of imprisonment for the large number of women who were incarcerated following the criminalization of prostitution, abortion and sexual relations between Aryan Germans and non-Aryans, as well as political adversaries. (A Holocaust Crossroads: Jewish Women and Children in Ravensbrück, edited by Irith Dublon Knebel, 2010)

The women at Ravensbrück were starved, frozen, beaten, worked to death, hanged, shot, poisoned, murdered with lethal injections and gassed. Estimates of the final death toll range from about 30,000 to 90,000; because so few SS documents pertaining to the camp survive the mass destruction of evidence — both human and documentary — nobody will ever know the exact figure. As thousands upon thousands of women poured into the camp, it became a cesspool of filth, disease, and death.

Additionally, Ravensbrück was the site of diabolical experiments conducted on eighty-six young, healthy women in their twenties – 74 of whom were Polish political prisoners — one as young as 16 – who were subjected to surgical experiments that either killed them or mutilated them for life.

Yet, for all its horror, Ravensbrück was overlooked by historians. Its history was shrouded in shadows. Thousands of its official records and documents had been destroyed; some were burned along side with the human victims in the crematorium during the last days of the war — even as the dead bodies from the gas chamber were piled high. Sarah Helm, a British journalist has written a book published under two titles in 2015: Ravensbrück: Life and Death in Hitler’s Concentration Camp for Women and If This is a Woman: Inside Hitler’s Concentration Camp for Women. The second title comes from the Primo Levi poem “If This Is a Man” in which he reflects on the year he spent in Auschwitz:

“I am constantly amazed by man’s inhumanity to man.”

“Consider if this is a woman, Without hair and without a name, With no more strength to remember, Her eyes empty and her womb cold, Like a frog in winter. Never forget that this has happened.”

“Ravensbrück was an abomination that the world has resolved to forget.” (Francois Mauriac) The major reason that the history of Ravensbrück remained shrouded was its 45-year post-war isolation under the Communist East Berlin regime which barred access to Western scholars to its documents. During the Communist regime, East German bureaucrats created a history of the camp that served its political agenda by selecting only “proletarian” heroines while excluding all the women who were affiliated with religious anti-Nazi groups, such as Catholics, Jehovah Witnesses, Jews, and non-Communist Western resistance groups. The East German regime also falsified the Red Army’s role as “liberators” of Ravensbrück survivors. In fact, the abominable “liberators” raped every woman and girl in sight disregarding even their emaciated physical condition.

Jewish historical scholarship of the Holocaust – Shoah – remained for decades a self-contained world, mostly the domain of Jewish historians who focused on gathering and analyzing the documents that articulated the Nazi policies, decisions, and measures that led to the most systematic and sustained genocide. They did not trust the testimonies of survivors’ recollections; they formulated a more or less sexually neutral perspective about the suffering of the victims. In the collective memory of the Holocaust, Auschwitz and the other major death camps in the East are the embodiment of Nazi crimes against humanity; and the implementation of die Endlösung der Judenfrage — “the Final Solution to the Jewish Problem” which explicitly aimed at the mass extermination of the Jewish people in gas ovens relatively quickly. Helm argues provocatively that “just as Auschwitz was the capital of the crime against Jews, so Ravensbrück was the capital of the crime against women.”

Ravensbrück and the other SS concentration camps that were located inside Germany were considered marginal and of far less interest. This perception is rooted in the Nazi decision to execute its mass murder operations in the East where they constructed the machinery for the industrialized extermination of millions of Jews. The decision to “outsource” the Final Solution to the East provided Germans with a “plausible deniability” defense whereby they denied having known about the Nazi atrocities committed far away. (A Holocaust Crossroads: Jewish Women and Children in Ravensbrück, edited by Irith Dublon Knebel, 2010)

The camp location belied the Germans’ claimed ignorance about its existence; Ravensbrück was situated in the Fürstenberg Lake District in Germany, just 50 miles north of Berlin. The ever present smoke and smell from its crematorium was impossible for nearby villagers to ignore. Ravensbrück was dismissed by historians and mostly forgotten as an incongruous outlier; it did not fit the Holocaust narrative. It was a women’s camp where Jewish women were a minority (15% to 20%) at all times, primarily because they were transported to Auschwitz to be gassed. Adding to its marginalization was that a significant minority of lesbians were there, among the camp guards and inmates. (Rochelle Saidel. The Jewish Women of Ravensbrück, 2004; Helm. Ravensbrück 2015)no one examined the camp’s history in depth until the late 1990s.

Ravensbrück played an essential role in the history of the Holocaust

The belated examination of this history shows that Ravensbrück played an essential role in the history of the Holocaust; both at the start and in the final months of frenzied mass extermination of Jewish women. At Ravensbrück prisoners’ status was determined in accordance with the Nazi hierarchical racial policy. The camp was used as a model for the newly established women’s camp in Auschwitz, which was first under the command of Ravensbrück. And when Auschwitz was dismantled, the remaining Jewish women were transported to Ravensbrück to be gassed in a portable gas chamber.

In addition to Helm’s book, two other major examinations of the camp restore it to memory by bearing witness on a human scale: Jewish Women Prisoners of Ravensbrück: Who Were They? (2008) by Judith Buber Agassi and A Holocaust Crossroads: Jewish Women and Children in Ravensbrück (2010), edited by Irith Dublon Knebel.

Ravensbrück was tucked away behind a forest of pine trees, birches, on the shores of an idyllic lake to hide its existence. Heinrich Himmler, chief of the SS, the overseer of SS extermination and slave labor camps — and the principal architect of the Final Solution — had a particular interest in the camp, dropping in on occasion as he visited friends and his mistress and their baby nearby. Ravensbrück was built by slave laborers from Sachsenhausen and opened in 1939, as a prison for “deviant” women whom the regime considered political enemies.

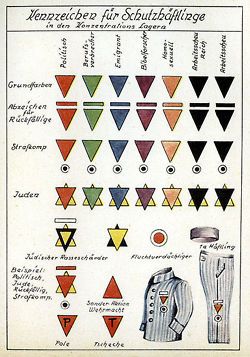

Each “deviant” category was assigned a color coded triangle patch sewn on each woman’s uniform: red signified political; purple for Jehovah’s Witnesses; black for “asocial” which included Gypsies, lesbians and prostitutes; green for criminal; and yellow for Jews. A few Jewish prisoners were also classified as political, they were identified by both a red and a yellow triangle, arranged as a Star of David. “Jewish women were always set apart by their “race” on camp lists, even when they were also in another category.” ( Rochelle Saidel. Ravensbruck Women’s Concentration Camp)

Jehovah’s Witnesses were considered enemies because they refused to salute “Heil Hitler” or join the war effort. As the war escalated, the camp population expanded to include petty criminals, Gypsies and Jewish women. Inasmuch as the intent was to “cleanse” Germany of all Jews, for most Jewish women Ravensbrück was a stop-over. An estimated 26,000 Jewish women passed through or were murdered at this camp.

The camp was built to hold 5,000 women, but expanded to detain as many as 45,000 Throughout its six year existence, from 1939 to 1945 its camp grounds were expanded to encompass 40 sub-camps that were spread across a wide area; its inmates were used for slave labor. From 1942 onward, a diverse group of women from 27 countries were incarcerated at Ravensbrück: the largest group was Polish (30%); next, Russian and Ukrainian (21%); followed by German and Austrian (18%); Hungarian, including Roma and Sinti Gypsies (8%); French (7%); Belgian, Swedish and Danish women as well as some 12 British women.

A separate camp for 20,000 men was opened in April 1941, and another for juvenile delinquents. Uckermark “Youth Camp” housed 1,000 “asocial” teenage girls, aged 14 to 21 who were subjected to similar despicable malnutrition and hygienic conditions; they were also subjected to pervasive physical and psychological terror as the women in the main camp. (A Holocaust Crossroads; Jewish Women and Children in Ravensbrück edited by Irith Dublon-Knebel, 2010) There were additionally about 800 children aged two to 14.

Quantitatively, the murder tally at Ravensbrück was not anywhere near that of Auschwitz where within six weeks during the summer of 1944, 400,000 Hungarian Jews were gassed; or Treblinka where between 870,000 and 925,000 Jews were murdered between July 1942 and November 1944. At Ravensbrück, an estimated 30,000 and 50,000 women died from disease, from frost, starvation, beatings, executions (in a special shooting gallery), lethal injections and medical experimentation.

Unique inmate composition sets it apart

The unique multi-national composition of Ravensbrück inmates included many academics, writers, artists, actors, singers, doctors, politicians, who had ties to underground résistance groups.

“Ravensbrück was not only a juncture within the history of women’s persecution, the Holocaust, and the history of Jewish women during the Holocaust, but it constitutes a social crossroads as well. Women from different social strata, national, ethnic and religious origin were forced to live together under the most extreme conditions.

In addition, these women lived within the social system of classifications created by the SS that was utilized as a major tool of their regime. The hierarchy of this social system, which determined the living conditions and relations among the prisoners, was based, as Wolfgang Sofsky explained, on the prisoners’ proximity to the SS centre of power, at one end, and death at the other.

The prisoners’ location within this hierarchy was first and foremost determined by their racial and ethnic affiliation, followed by national category, political worldview, religion and degree of supposed social deviation. Closest to the centre of power were German political and criminal prisoners, who were used by the SS in the self-administration system of the camps as prisoner-functionaries…Not only were Jews located at the bottom of the scale because they were sentenced as a group to annihilation… The ‘annihilatory pressure’ and daily existential struggle conditioned interpersonal relations and relations among the groups. ” (Knebel. A Holocaust Crossroads, 2010)

Among the unusual inmates was an eccentric, wealthy countess, Karolina Lanckoronska, who was a professor of art history and member of the Polish underground. (Lanckoronska. Michelangelo in Ravensbrück: One Woman’s War Against the Nazis, 2008). Another was Elizabeth de Rothschild, Catholic wife of Baron Philippe de Rothschild who was sent to Ravensbrück in 1941 where she died of typhus shortly before liberation (Obituary of Philippine de Rothschild, 2014); another was Gemma La Guardia Gluck, Mayor Fiorello La Guardia’s sister.

Another prisoner at the camp was Geneviève de Gaulle, niece of Charles de Gaulle (who was kept part of the time in isolation when SS Chief, Heinrich Himmler decided to keep her alive as a possible exchange prisoner). Himmler’s own sister, Olga was interned for a short time because she had had a love affair with a Polish officer in Warsaw. (Frank Morrison. Ravensbrück: Everyday Life, 2000)

Germaine Tillion, French ethnologist / anthropologist at the Musée de l’Homme, was another prisoner interned at at Ravensbrück. During her 14 months there, Tillion secretly recorded the identities of the principal SS personnel which she coded as recipes and hid the information until she was rescued by the Swedish Red Cross. Tillion also smuggled a roll of film showing the deformed legs of the Polish “rabbits.” Her published eye witness report of daily life at the camp, including information about Jewish inmates was published in French in 1946; it serves as the earliest detailed eyewitness accounts.

She described Ravensbrück as: “a world of horror that was a world of contradictions: more terrifying than the visions of Dante, more absurd than a game of snakes and ladders”. She said that while there, she lost the will to live. “Ravensbrück was an abomination that the world has resolved to forget.” (Francois Mauriac)

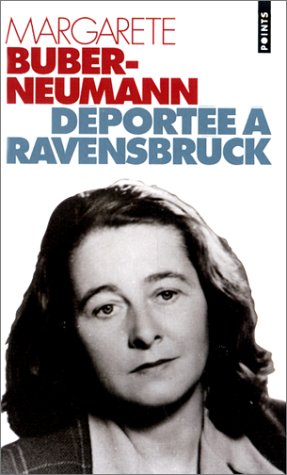

Margarete Buber Newmann, a German Protestant Communist who married Rafael Buber, son of the famous Jewish philosopher, Martin Buber, with whom she had two daughters. After they divorced she married a leading German Communist, Heinz Newmann who soon lost his footing within Communist party intrigue, who was shot dead in prison. Margarete was convicted of “counter-revolutionary agitation” and imprisoned in several Soviet prisons before she was transported (in 1940) with about 350 other female prisoners from the horror of Stalin’s Gulag, to the horror of Ravensbrück. But being German, she was treated fairly well; and was put in charge of the Jehovah’s Witnesses block.

Her book, Under Two Dictators: Prisoner of Stalin and Hitler (1949; re-issued, 2008), is considered a significant account for historians because it was written so soon after the war; because it describes imprisonment under both Hitler and Stalin; and because it pays particular attention to the experience of women prisoners. She describes the regimentation at Ravensbrück as “Prussian thoroughness” with its authoritarian guards, twice-daily roll-call, identical striped dresses and white kerchiefs, and “neurotically enforced cleaning routines.” When she was released in April 1945, days before most of the remaining prisoners were forced on a death march; she rushed to reach Bavaria to be reunited with her family when she had to fight off an attempted rape. (London Review of Books, 2008)

On May 27, 2015, both Geneviève de Gaulle and Germaine Tillion were symbolically interred among 74 men in the Panthéon mausoleum of honor. (French President Francois Hollande Adds Resistance Heroines to Panthéon, The Guardian, 2015) [See a collection of annotated photographs showing both victims and villains at: Ravensbruck]

Sexual debasement & dehumanization begins upon arrival

An objective of Nazi concentration camps was to debase every vestige of sexuality and humanity of inmates. All Ravensbrück survivors remember the shock upon arrival, and the terror instilled by the “welcoming” shouts of the SS guards and the barking, biting dogs during the 25-minute walk from the train station to the camp. Worse still was seeing the other, bald, skeletal inmates for the first time; so terrifying was the sight of them, that some even cried out to the guards to “keep these monsters away.”

Sexual debasement was part and parcel of the SS scheme to divide and rule among inmates and destroy their dignity. From the moment of arrival, women were humiliated and violated; they were forced to strip naked; women had their head and pubic hair shaved; they were examined vaginally, and assigned a “deviant” identification symbol — all the while lewd SS men leered and jeered. A middle class woman born in the early twentieth century – whether she was French or Polish Catholic, or Jewish – had an ingrained sense of modesty about their bodies. That modesty was deliberately under attack; the women had to undergo tests for venereal disease including a vaginal exam. Since infected women would receive no treatment, and the instrument used was not cleaned or sterilized between patients, the process was clearly done to humiliate the prisoners.

In personal memoirs, women relate incidents that highlight the traumatic nature of camp internment with its radical assault on their sense of normality.

“Clip go the shears, and the last shreds of humanity…women fall victim to SS sadism…When the job is done, the fixed stare of extinguished eyes looks out, unseeing, from under the bald skull…the blow resound and we are practically pushed into the actual shower room…With our freshly-shaven bald heads, shivering in this cold February afternoon…dehumanized, disfigured host of scarecrows.” (Eva Langley-DanosPrison on Wheels: From Ravensbrück to Burgau, 2000)

“Our turn comes; we must go to the showers. There like all those of the preceding convoys, we will be odiously searched and stripped. Completely nude, we wait to undergo the “hairdresser’s” exam. With anxiety, I watch Isabelle, now on the hot seat… Behind us a little Bretonne cries and is ashamed of her shaved skull that makes her unrecognizable.”

“With no consideration for the fact that I’m a virgin, he shoves the speculum violently inside me, shortly followed by his rubber-clad finger… A bit calmer after talking to other young women in my convoy who underwent the same experience, I realize that my virginity must be a thing of the past.” (Maisie Renault quoted by Margaret-Anne Hutton. Testimony from the Nazi Camps: French Women’s Voices, 2005)

The naked prisoners were then marched into an open courtyard where they waited in all weather. The women were denied access to rudimentary washing and hygiene which was another form of debasement. Each new prisoner who arrived at Ravensbrück was required to wear a color-coded triangle that identified her by category, with a letter sewn in the triangle that showed the prisoner’s nationality. In her book, The Jewish Women of Ravensbrück (2004) Rochelle Saidel addresses in detail the issues of personal hygiene, nudity, and menstruation in the camps. Women survivors’ memoirs vividly describe the lack of opportunities for maintaining personal hygiene; they were unable to wash or brush their teeth, and access to latrines was restricted. These restrictions were a radical deprivation of inmate’s most basic needs.

The dreaded twice-daily roll-calls

Survivors who had been interned a Ravensbrück and other concentration camps regarded the regimentation in Ravensbrück as especially severe; in particular, the endless twice-daily roll-calls that began before dawn, during which prisoners had to stand in line for hours in the bitter cold while female guards dressed in black capes and shiny boots kicked and lashed them with whips. Many women collapsed from exhaustion were taken to their death. Others froze to death where they stood. Those who were deemed fit for labor would be directed to one of the slave labor gangs where they were worked to exhaustion, ultimately to death.

The sadistic brutality of the guards was matched by the camp doctors. Dr. Walter Sonntag, senior doctor, exercised enormous power over the women during the ever constant selections – which were a death sentence or selection for experimentation.

“On his first day they all watched as he passed down the line of waiting women, kicking the weakest with his boots, or lashing out with his stick at any cries of pain. What horrified the women was not only his brutality; it was the smile on his face.” (Helm. Ravensbrück, 2015)

Abhorrent macabre medical Experimentation

Ravensbrück was conveniently situated and its Revier (hospital) staffed with doctors and nurses. Experimental medical atrocities were conducted under the watchful eye of chief of SS chief Heinrich Himmler who was fascinated by medical experimentation, and his approval was necessary for every deadly experiment conducted at SS concentration camps.

Five miles from the camp was the Hohenlychen clinic; originally built as a sanatorium for children with tuberculosis. Beginning in 1933, it served as a clinic for sports medicine, providing therapies for athletes; later high ranking wounded soldiers were treated there. It was frequented by the luminaries of the Reich. Hohenlychen director, Dr. Karl Gebhardt, was Heinrich Himmler’s personal physician; he was also Chief Surgeon of the Reich Physician SS and Police; as well as the President of the German Red Cross. Gebhardt was a personal friend of Max Huber, President of the International Committee of the Red Cross in Geneva.

Gebhardt masterminded the ghastly surgical experiments conducted on 86 young healthy women inmates at Ravensbrück; of whom 74 were Polish political prisoners were nicknamed “kroliki’ “kaninchen” “lapins” or “rabbits” because they were used as human laboratory animals. The experiments were designed to maim and cripple healthy human beings. Some died as a result, some were executed, and some survived. (Read their story in our post “lapins” living symbols of medical atrocities and Ravensbrück 74 Cases of Medical Experiments Conducted on Polish Political Prisoners, a website maintained at the University of Toronto )

Gebhardt masterminded the ghastly surgical experiments conducted on 86 young healthy women inmates at Ravensbrück; of whom 74 were Polish political prisoners were nicknamed “kroliki’ “kaninchen” “lapins” or “rabbits” because they were used as human laboratory animals. The experiments were designed to maim and cripple healthy human beings. Some died as a result, some were executed, and some survived. (Read their story in our post “lapins” living symbols of medical atrocities and Ravensbrück 74 Cases of Medical Experiments Conducted on Polish Political Prisoners, a website maintained at the University of Toronto )

While “the world resolved to forget,” the survivors of Ravensbrück did not forget

In February 1942, 1,600 predominantly Jewish women were transported to Bernburg, a nearby T4 “euthanasia” killing center. The action, coded “14F13,” was a test run on German soil of systematic implementation of the Nazi “Final Solution” – aimed at exterminating all Jews. In September 1942, Himmler ordered the remaining Jewish prisoners in Ravensbrück to be sent to Auschwitz, to make the camp Judenrein — “cleansed” of Jews. (Rochelle Saidel. The Jewish Women of Ravensbrück, 2004).

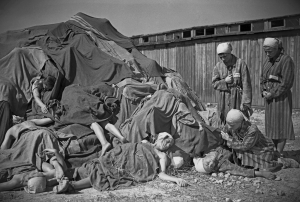

However, in the fall of 1944, thousands of Jewish women arrived from Hungary, but there was no place to put them. A big tent with a straw floor was erected where the women were left to perish with virtually no water, no food, or blankets and no toilet facilities. They lay in their own excrement in the freezing cold. They died in masses. (Saidel. Jewish Women’s Archive Encyclopedia)

In January 1945, when Germany was retreating from the Eastern front and Auschwitz was being evacuated, a portable gas chamber was constructed at the “Youth Camp” which from then on served as the Ravensbrück extermination center. In late March 1945, 5,600 women prisoners were transported from Ravensbrück to be gassed at Mauthausen and Bergen-Belsen. Between February and April 1945 an estimated 6,000 women were marched out from the main camp into the woods where they were murdered; they were either shot or exterminated in a portable gas chamber built when . In April 1945, about 20,000 women, as well as most of the remaining male prisoners, were evacuated and forced on a death march toward northern Mecklenberg.

When the war was almost over, the camp became a frenzied, mass murder apparatus to which women who had survived the horrors of Auschwitz were transported to be exterminated at Ravensbrück . It was one of the most terrible women’s prison; yet it has remained in the shadows. Some historians believe that the labeling of Ravensbrück as a “slave labor” camp contributed to its marginalization. In reality, for many thousands of women, slave labor was but a temporary reprieve on a train headed toward death. Prisoners referred to Ravensbrück as a death camp. Survival depended to a large extent on luck and solidarity (Helm, 2015; Judith Buber Agassi. Jewish Women Prisoners of Ravernsbrück: Who Were They? (2008); Rochelle Saidel. 2004

Forgotten archive of Ravensbrück survivors’ testimonies

Incredibly, thousands of handwritten survivors’ testimonies, diaries, photographs, lists of names and prisoner transports, and 500 oral interviews recorded during one year, were first stored at Sweden’s Lund University; in 1949 the archive was moved to Stanford University where the documents remained unedited and untranslated. In 2004 the archive was donated to Lund University which has finally translated, cataloged and edited the material, Voices from Ravensbrück and made it accessible in 2014. Those testimonies were given by some of the 7,500 inmates of Ravensbrück who had been rescued in the spring of 1945 by the Swedish Red Cross in the so-called Operation “White Buses” which Count Folke Bernadotte had personally negotiated.

“What’s so exceptional about these testimonies is that they were given in real time, while the survivors’ wartime experiences were still fresh in their minds, not years or decades later.” In all, more than 21,000 former concentration camp prisoners who were rescued came to the southern parts of Sweden. (Tom Tugend. Swedish University to archive Ravensbrück survivors’ stories, Jewish Journal, August, 2014)

[The following five posts describe the brutal milieu in which selection for slave labor is considered a lucky break when the alternative is selection for extermination; Training center for the SS guards; Medical staff atrocities: experimentation & extermination; and “lapins” living symbols of medical atrocities; Disposable slave labors; disposable children; bonding, solidarity, acts of resistance; the final weeks of extermination and the last minute Swedish “White Bus” rescue Operation that saved 15,000 human beings.]

Brief Current Ravensbrück Bibliography

A Holocaust Crossroads: Jewish Women and Children in Ravensbrück, edited by Irith Dublon Knebel, 2010

Judith Buber Agassi. Jewish Women Prisoners of Ravensbrück: Who Were They? 2008

Jeanne Armstrong. Community, Survival and Witnessing in Ravensbruck, 2011

Tom Clark. “The Beautiful Beast”: Why Was Irma Grese Evil? Working paper, Sociological Studies, University of Sheffield, 2012

Jarek Gajewski. Ravensbrück 74 Cases of Medical Experiments Conducted on Polish Political Prisoners website maintained at the University of Toronto.

Peter Norbert Gengler. Exhibiting Antifascism: Ravensbrück And The Ambivalences Of East German Commemoration, 1945-1989, a thesis, University of North Carolina, 2013

Sarah Helm. Ravensbrück: Life and Death in Hitler’s Concentration Camp for Women, 2015; also under the title, If This is Woman, excerpts

Kathrin Kompisch. Perpetrators: Women Under National Socialism, translation, 2009

Gemma La Gurardia Gluck. Fiorello’s Sister: Gemma La Guardia Gluck’s Story, 1961; reissued, 2007 Karolina Lanckoronska. Michelangelo in Ravensbrück: One Woman’s War Against the Nazis, 2008 Elissa Mailänder. The Violence of Female Guards in Nazi Concentration Camps (1939-1945), 2015, Online Encyclopedia of Mass Violence

Jack Morrison. Ravensbrück: Everyday Life in a Women’s Concentration Camp, 1939-45, 2000

Rochelle Saidel. The Jewish Women of Ravensbrück, 2004

Wendy Sarti. Examining Why Sadism Violence and Identity, The Group and the Common Enemy, in Women and Nazis: Perpetrators of Genocide & Other Crimes During Hitler’s Regime (1933-1945) 2011

Ulf Schmidt. The Scars of Ravensbrück: Medical Experiments and British War Crimes Policy, 1945-1950, German History, 2005; also publihsed in Atrocities on Trial: Historical Perspectives on the Politics of Prosecuting War Crimes, Edited by Patricia Heberer and Jürgen Matthäus, 2008

Alette Smeulers. Female Perpetrators: Ordinary or Extra-Ordinary Women? International Criminal Law Review, 2015

Robert Sommer. Concentration Camp Bordello: Sexual Forced Labor, 2009

Vivien Spitz. Doctors From Hell: the Horrific Account of Nazi Experiments on Humans, 2005

Germaine Tillion. Ravensbrück, 1997

Karen Iris Tucker. Life Inside the Ravensbrück Concentration Camp for Women, Slate, April, 2015

Tom Tugend. Swedish University to archive Ravensbrück survivors’ stories, Jewish Journal, August, 2014

Martyn Whittock. A Brief History of The Third Reich, 2011