Disposable slave laborers; disposable children

Pervasive violence, brutality and murder, combined with hard labor, overcrowding, disease, and starvation systematically limited the number who survived Ravensbrück. The coercive hierarchy of the camp encouraged the guards to brutalize and terrorize prisoners.

Paradoxically, women conscripted to work as slave laborers considered themselves lucky; they avoided being “selected” and transported to an extermination camp. The women worked 12 hours a day; they worked in various industrial plants in the camp such as garment factories producing military uniforms for the SS; or in one of its satellite munitions and other war-related factories. Some worked as farm and forest workers; others worked in the laundry, or kitchen; and some worked as personal servants of the guards — as maids, hair dressers, and dressmakers. Some women worked in camp administration, and some worked outside the camp in the nearby town of Fürstenberg.

The worst assignments were for hard outdoor labor; which included cutting trees, cutting ice, moving logs, building roads, unloading cargo from boats on the lake, and carrying dead bodies from barracks to crematoria. Some women were used like animals, forced to pull a huge roller to pave the streets; requiring a team of twelve to fourteen women to pull what they called “Walzkommando.”

Jewish inmates were segregated from and strictly forbidden any contact with other nationalities; they were subjected to the worst conditions and were assigned to different work details; their death rate far surpassed that of all other national groups. (Rochelle Saidel. The Jewish Women of Ravensbrück, 2004) By the war’s end, only 700 Jewish women survived.

Among the survivors was Gemma La Guardia who was treated as a “special prisoner” not subjected to the worst conditions that Jewish prisoners endured. Indeed, in her book, Fiorello’s Sister: Gemma LaGuardia Gluck’s Story, she noted:

“We’re all treated badly, but these poor French and Jewish women were brutally treated and misused. They had to work from early morning until night doing outside work, digging roads, cutting wood, in all kinds of weather… Jewish women had the dirtiest work to do; their block was the most unhealthy and dirtiest with no electric lights. They were treated like animals and not like human beings. Because the Jewish prisoners were subject to the harshest treatment, they constituted the largest group of those who perished at the camp.”

Siemens AG was a major player and profiteer from the Nazification of Germany; it employed slave laborers for its factories manufacturing munitions, electrical equipment and V-1 and V-2 rockets; and rumors persist that Siemens manufactured the gas chambers used at the death camps.

At the factory next to Ravensbrück, the women conscripted as slave laborers were kept on a starvation diet while assembling electrical parts. The company’s skeletal remains at Ravensbrück are clearly visible from the remains of its hilltop factory, located within eyesight of both the gas chamber and crematorium chimney – less than 300 yards away.

“The skeleton of an old workshop stands, and in the dip below are the old rail tracks…Also clear to see are the wooden trails along which trucks carried women to the gas chamber once they were ‘taken off the lists’ as too weak to work.”

“Anni Vavak, an Austrian-Czech prisoner, described how [..] trucks loaded with half-naked women driving from the Youth Camp, past the Siemens plant headed to the gas chamber… Selma van de Perre and other survivors recall selections for gassing taking place at the Siemens plant itself during the last months.” (Helm. Ravensbruck, 2015, p. 652)

There is no sign or memorial to commemorate Siemens’ plant site where thousands of women had been brutalized as slave laborers. After the war Siemens denied profiteering from slave labor; denied ill-treatment of those laborers; denied it made gas ovens for use in concentration camps; and has continued to deny access to its detailed copious archive. Two Siemens directors who were SS members committed suicide in 1945, no doubt because they anticipated war crimes trials. And the Siemens manager at Ravensbrück, Otto Grande, disappeared without a trace. (Helm. Ravensbrück, 2015)

Sarah Helm relates that during the British de-Nazification case against Siemens’ head of personnel, charges were made about the brutal abuse of prisoners and claims were made that Siemens “made gas ovens for the concentration camps.” She writes that a British adjudicator noted that Siemens’ defense statement was “rather wooly,” but there was no concrete evidence to support the claims. She notes that the incredulity of Siemens’ staff claimed ignorance about the existence of “gas ovens” or that workers in the Ravensbrück factory were gassed, undermines their credibility. The evidence may likely be hidden away within the Siemens archive.

Today, Siemens is worth approximately $89 billion and employs 370,000 people in 190 countries. The company owns half of Bosch Siemens Hausegeraete (BSH), the home appliance manufacturer. In 2001, Siemens sought to trademark the infamous name “Zyklon” for use in marketing a range of home appliances – including gas ovens. (Siemens’ Branding Gaffe, Forbes, 2002; Siemens Retreats Over Nazi Name, BBC News, 2002) It did not occur to the company that Zyklon is forever associated with the poison gas that was used in to kill tens of millions of men, women, and children in the Nazi death camps.

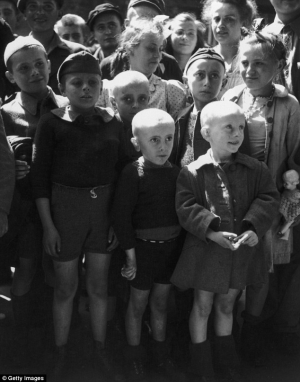

Children at Ravensbrück

Children at Ravensbrück

A “Youth Camp” was built for girls and young women was constructed that housed more than 800 children aged two to 16; and 1,000 teenage girls. (International Tracking Service) Some of the children had accompanied their mothers to the camp; others, about 800 were born at Ravensbrück. Some were listed in the birth register, others were not. During the final months of the war, the Youth Camp was turned into an extermination center with a portable gas chamber.

Children’s fate was determined based on shifting policy and racial hierarchy. Jewish children arriving with their mothers were transported with their mothers to be gassed at Auschwitz or Lublin. The children who were born in Ravensbrück, were all conceived before the mothers were arrested. Jewish and Gypsy infants born in the camp were drowned or strangled with their mothers watching. Slavic women and women impregnated by Slavic men – Polish, Russian, Yugoslav, etc – were forced to undergo an abortion; even in the eighth month. But in 1944, an influx of (predominantly) Polish women arrived, many of them pregnant, and they were allowed to give birth.

The first 20 babies were well treated, the mothers given a glass of milk after delivery. But within days, orders were given to suspend the extra rations; the babies were to die of starvation. The mothers screamed and pleaded, almost went mad, but to no avail. The mothers had to go to work; most could not produce milk. A babies’ room was built where the babies were deprived of nourishment and blankets; they were laid out head to foot “like sardines,” as a French prisoner described them. Within 30 days the first 100 babies died. (Helm, 2015)

If the father was of “higher” western nationality, the woman was allowed to carry the baby to term. But since no care was give either to the mother or the child, both frequently died; the mother of hemorrhaging and infections; the babies of starvation. (Caroline Moorehead. A Train in Winter: A Story of Resistance, Friendship and Survival,

Children’s survival and life span varied: “Some would live a few days, others a few weeks or months, a few several years. [..] the mother was not allowed to bring the child to work, but she had to bring it whenever she reported for a roll call.” (Kristian Ottosen. The Women’s Camp: The History of Ravensbrück Prisoners, ; Chapter: The Children in Ravensbrück translated in 1991) Ottosen relates an incident in which the head nurse threw a newborn infant into a red-rot oven! On a different note,

“The children quickly got to know the pulse of the camp. We could see bigger and smaller children play roll call and selection for the gas chamber and transport. They stood in a row and one of them reprimanded the others and shouted at them and called ‘Achtung! (‘Attention’). The children usually stayed behind the big laundry. The child who gave the orders pulled one of his playmates after another out of the row, and ordered them to get into the ‘gas oven’.

The ‘gas oven’ was an old centrifuge that had been discarded by the laundry and was standing outside against the wall. Its diameter was large and it was studded with many holes and covered by a lid. The children played so intensely that the eyes of those who were pushed into the centrifuge and had the lid slammed shut over them, were filled with fear.” (Prisoner in Ravensbrück” by Lise Børsum quoted by Ottosen)

Gypsy children were subjected to sterilization experiments. Of the 600 children born at Ravensbrück between Sept. 1944 and February 1945, only 40 survived. But most of these remaining children were rounded up and taken to Bergen Belsen to be killed. (Helm. Giggling Over Genocide, Daily Mail, 2015)